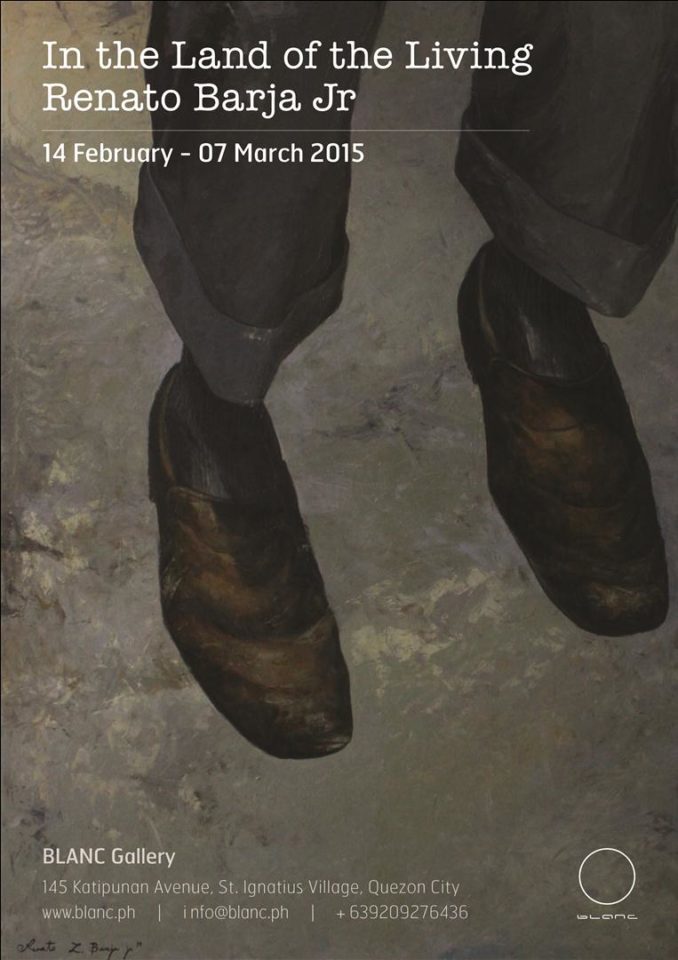

In the Land of the Living

Renato Barja Jr.

Through painting, an image persists from the known world, having been seized and interpreted via oil, pigment, and brushstrokes across the surface of a canvas by the artist’s hands. A ‘slice of life,’ it is most often called, through the thoughtful rendition of moments that are part of the everyday. Captured moments—artists would refer to these as a sacred instant, an unforgettable scene, or even as an epiphany, preserved in memory and materialized through their art.

Many artists—painters, photographers, filmmakers, and writers alike—have talked about that sacred moment: about ‘capturing’ a particular experience or scene, and how it is immortalized through art. This is an inherent agenda, given that we move through these fleeting moments, and move through our own ephemeral thoughts.

But for Jojo Barja, when asked about these moments in his poignant, tranche de vie paintings, the acquired images are all about seeing, and not capturing; these are about the moments that persist when we incessantly look for what is out there. It is about looking at reality, not taking from it. It is not an act of acquisition but a process of transference, which takes place during the jolt of inspiration—he sees his subjects and his subjects look back. In his moving portraits, Barja insists, that if one only looks hard enough, these faces will present themselves in all their essence.

Jojo Barja’s latest exhibition at Blanc Gallery, In the Land of the Living, recreates a world through seeing: his paintings unfold like an eyewitness’s account of his plight alongside the common folk, who have endured the anomalies and alienation of modern life, people who have decided to live on despite the land’s persistent call for desolation. It is projected through an anomaly of tones inside the frame—the damp hues of their skin in blue and grey juxtaposed by lively colors of bright red and green from an ornament of props these corpse-like figures possess. His portraits are also livid in their appearance, creating a sense of stupor amidst their bold gestures: a father cuddling his child, a construction worker holding on to a lone flower stem, children standing pompously from the throes of their innocence—these are characters that pervade the artist’s sight. These are characters that have been spotted and seen, and are persistently viewed in the mind’s eye.

Looking is a process that has affected Barja at an early age. Through his mother, who constantly told him to ‘look,’ he has acquired the habit to latch onto appearances, not as a way of judging, but of perceiving meaning beyond one’s intuition. He has learned early in childhood the discrepancies of the visual realm. Having lived in an isolated community—sanitized and neatly arranged, while at the same time adopting for his home the depressed area on the other side of the wall, he has seen the stark contrasts of the neatly arranged houses against the volatility of shanties sprouting from the ground, the clear, white tenements against the burnt tones of plywood and rust, and the orderly life against the quandary found in freedom and pleasure.

In In the Land of the Living, Barja’s art has evolved via another exodus—as witness to the aftermath of a typhoon, the great flood which had submerged the city, where his colors have turned from ochre and sienna to the bloated hues of blue and grey. While wading through the flood a realization takes place: how everything can be quickly submersed, and how delicately the line is drawn between survival and extinction.

The pattern of images and sequence of sceneries from Jojo Barja’s latest works are vestiges to this idea of clinging on to the fine thread that separates life and death. And through these depictions of life he tries to infuse more life by constructing dioramas and soft sculptures. Each of the stories he has to tell through painting have their corresponding figurines, sculpted in epoxy and adorned with found objects, with others molded in fiber and stitched cloth. This is the world Jojo Barja has reconstructed for us to see—a world sulking in drab tones, and long faces, yet disrupted by sudden flashes of bright colors, hinting some hope against their quiet desperation. And more importantly, for the hope it imparts—is the hope that there is still room for a new way of depicting the plight of the common Filipino.

Cocoy Lumbao

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION