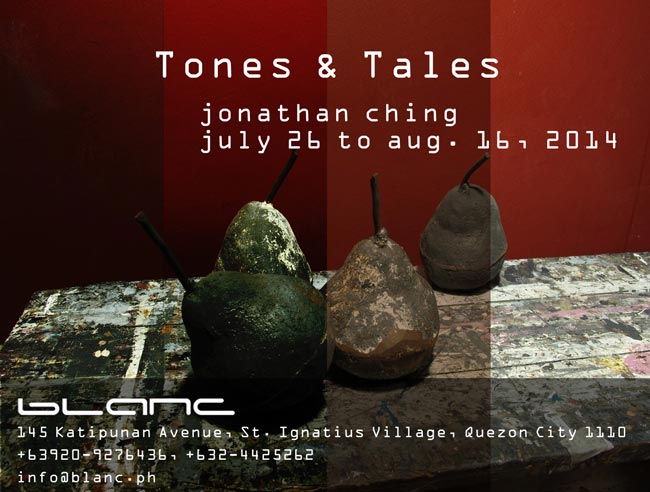

A romantic fabulist with an Impressionist’s love for viscid swirls of pigment, Jonathan Chingweaves stories from snatches of songs, wilted flowers, and the imagined lives of famous paintings and people.Composed of six works, Tones and Talesbrings the mini-fictions in Ching’s mind out into the open.

The title piece is a multi-panel timelapse that shows a yellow bouquet of mums in progressing stages of decay. Anode to mortality, Tones and Talessplinters off in different angles and compresses the lifespan of a blossom—from full bloom to fallen petals—into eight rectangular frames. Ching does Cubists one better by painting from multiple perspectives, not just spatial but temporal as well.

In Arena and Infinite Fiction, he spins stories from stolen canvases. In the first, Juan Luna’s Spoliarium is taken from its place of honor at the National Museum of the Philippines and istransportedto a ramshackle structure. The overhead view of the scene reveals how far Luna’s masterpiece has fallen. The defeated gladiator’s orientation is optically correct from the observer’s perspective—which means that in Ching’s invented storyline, the lauded painting has beenunceremoniously tipped on its side and left to rot ina narrow room with crumbling walls. Ching took Arena, the title of this painting, from “The Atrocity Exhibition,” a Joy Division song with pointed lyrics:

“Asylums with doors open wide, /Where people had paid to see inside, /For entertainment they watch his body twist/ Behind his eyes he says, ‘I still exist.’// In arenas he kills for a prize, /Wins a minute to add to his life. /But the sickness is drowned by cries for more, /Pray to God, make it quick, watch him fall.”

Revelatory of Ching’s motivations, the songis appropriate commentary for any form of entertainment that makes a public spectacle out of human misery (gladiatorial combat, for one).Attached to the center of the painting is a cartoonish explosion sign, an absurd addition that shatters the melancholy mood Ching deftly created with his palette.

Meanwhile, Infinite Fiction is a triptych that riffs on Edgar Degas’ Waiting, an early work from the French Impressionist’s ballerina-centric series. The purloined painting acts as a background for a troupe of lamps with empire shades flaring out like dancers’ tutus—a clever visual pun on Degas’ dancers. While Ching leaves the central panel open to interpretation, he exposes the frame of the Degas in the bookending panels to explicitly say that Infinite Fictiondoes indeed contain a painting of a painting, just like Arena.

Every work in the exhibition is a little world unto itself, which can unfold into a freewheeling flight of fancy thanks to the presence of teasing details, often sculptural. They Think We Grant Wishesis a portrait of British painter Cecily Brown based on a Todd Eberle photograph. Ching has gone down this road before with a four-panel painting of Julian Schnabel as seen from the lens of Annie Leibovitz. Continuing the journey he began with Schnabel, Ching shows Brown lying like a languorous goddess, sliver of skin exposed, in front of her vibrant canvases. Ching turns Eberle’s image into a shrine by placing a stainless-steel shelf just underneath the dollar sign on Brown’s shirt. Atop this shelf sits an offering of pears, swollen-shaped symbols of immortality and sensualityreflecting the worship accorded to contemporary artists of a certain stature. Through this intervention, Ching opens the door to discussions on art, celebrity, and money without overt judgment.

Big conversations make way for personal ones in the last two works included in Tones and Tales. Odiefeatures a dog enjoying a vinyl recording of The Clash. Ears perked and moist brown eyes open wide, the canine looks out of the canvas and pleads for attention. As is his wont, Ching affixes metal embellishments into the painting. Where the album sleeve of Give ‘Em Ropehad vultures feasting on the remains of a cowboy, the Odie version has a copper dodo. Pushed to explain this idiosyncratic replacement, Ching will say that the extinct bird is a memento mori.

The show comes around with Cathedral of Forgotten Dreams, another fractured work that leaps from flower to church lancet window to flower again. The limp yellow mums flanking the geometric centerpiece could very well have been plucked from the title piece, completing a disjointed reverie that circles back in on itself. For no rhyme or reason, cardinals,striking blue conchs, and miscellanylitter the wooden ledge that supports the piece. Like any good narrator, Ching doesn’t give away all of his secrets or over-explain himself. The emotional pull of his work lies in its pervasive sense of mystery.

mum— ll

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION