Tatong Torres

/1 Pleasant

Blanc Gallery

“plastic bag put over your head,

razor blades down your throat

drano in your veins

drano in your veins

splintered glass in your food

axe right through your skull

fire in your eyes

fire in your eyes

silver daggers in your throat

baseball bat in your face

fire in your lungs

fire in your lungs”

Drano was something of a mythical arsenic, a cheap household liquid toilet cleaner that can instantly kill without a trace, dissolving upon touch organs where its iridescent blue liquid flowed. Apparently, it became a popular murder method in the US as was opted by Michael Alig whose crime story was the basis for post-Home Alone Mcaulay Culkin starrer Party Monster. The method Alig used to murder his club partner Angel Melendez ran a similar inventory from the song – hammered, duct-taped, smothered, injected with Drano – but put a gruesome closure to it by decapitating the body and throwing the cut parts into the Hudson river. While serving his prison term, he made paintings. RuPaul’s Dragrace show producer, World of Wonder sells his club culture-inspired prison paintings online. Drano figured also in the high profile Hi-Fi murders where 3 US service men robbed a hifi shop in Utah and forced ingest Drano into their hostages. This was the first of murders that utilized such substance. This was in 1974. The song Drano In Your Veins was first released in 1975. In jangly guitars and equally jangly falsetto chorus, it reverberated the grating viscerality of a liquid dishwashing cleaner being flushed down one’s throat – blazing, flaring, steel upon steel. The Styrenes, named also after a chemical compound, was a band that existed under the radar whose members drifted to form other bands (like Pere Ubu) and went back again to record albums and play gigs intermittently up until the late 1990s. They were classified or associated with proto-punk, no wave, and post punk, namely because they utilized noise and some electronica, unconventional song structure, and were quite loud yet still retained some melodic appeal that triggers inevitable head bobbing despite the narration of a murder scene that also doubles as a murder tutorial.

The visuals of the incident being narrated in the song live on each time it is played, into a theater of instant re-enactments. They may vary in detail as they are conjured in imagination. What really happened? The incident has been distanced for us by time, by the band’s interpretation of the event, maybe even to an extent, by language and context, as Drano is not a popular household name in these parts, or is rather known here merely as muriatic acid or liquid sosa.

We are almost naturally drawn to images/incidents of deaths, accidents, diseases, decay. We swig lustful intoxication for such like liquid Drano. The more gruesome they are, the more we are intrigued, the more we tend to look more, to know more about it, despite the quelling retching instinct swelling up our throats, still we keep on swallowing. To look death straight in the eye, or like vultures or hyenas circling over carcasses. The putrid corporeality of our mortality luring us into shock and awe consumed by way of horror films, tabloid TV, crime fiction and websites like rotten.com and liveleak.com.

This phenomenon is enunciated theoretically as confronting the abject. Julia Kristeva in her book

Powers of Horror expounds on the subject of abjection as the state of being cast off, or as the process of separating one’s self, be it physical, biological, social or cultural, from that which one considers intolerable and infringes upon one’s ‘self’. Hence, the abject is the “me that is not me”. We see cadavers, diseased bodies, wounds, decapitated anatomy as a projection of a fear, a projection of the limits of our anatomies, a projection of our mortality creeping into our psych, a corporeal dread that we hide under the cloak of spectacle. It is a spectacle veneered through the sheen of mass media, art, photographs, and pop culture.

In her book Regarding The Pain of Others, Susan Sontag contends that “each situation has to be turned into spectacle to be real.” However “each situation” we are now confronted with had been an event distanced further from us by the frames of a photograph or a printed image or a pixilated digital feed. A thousand moreso when they are reproduced ad infinitum as Andy Warhol’s serigraph prints of a car wreck, in neon day glo colors even.

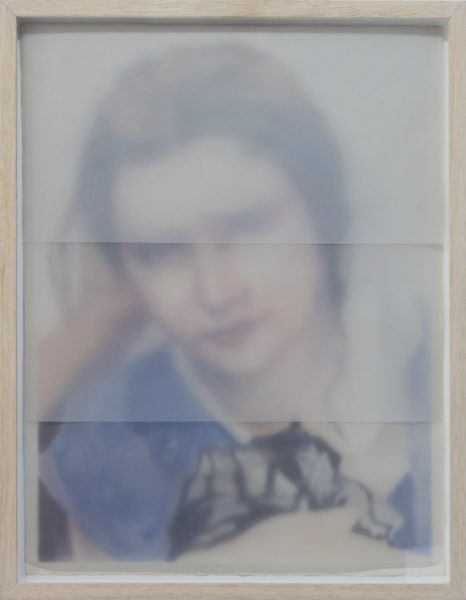

Tatong Torres riffs from the tragic demise of sacrificial visionary Franz Reichelt, a tailor with dreams of flying and had altruistic aims of providing safer equipment for aviators evacuating damaged aircraft. In pursuit of the 10,000 francs prize offered by the Aéro-Club de France, in exchange for a lightweight and safe parachute, Reichelt sets out one chilly morning of February in 1912 to test his prototype parachute of voluminous silk. Jumping from a height of 187 feet, from the Eiffel Tower’s first deck, he plummets fast towards the dirt, to the aghast crowd who were minutes ago were agog with wonder. Where Icarus’ tragedy resides in the realm of the mythic as his fall is immortalized as a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, lent more poignancy by the resulting poem William Carlos Williams wrote contemplating on the said painting – a reportage on a twice removed event with no spectators, the fall happening “unsignificantly” as daily life trudges on. On the other hand Reichelt’s fate has turned into some tragicomic farce, his fall witnessed by many and immortalized in film, played as newsreel then, now trivialized as an emoticon gif for the folly of old-timey technology. None more underlined when a workable and lightweight parachute had already been invented and successfully tested from a plane in flight by Gleb Kotelnikov, around the time of Reichelt’s death.

The larger than life canvas panel on which this was painted exalts the very spectacle of the event, for two seemingly impossible feats – flying like a bird, and being successful in it – but have badly failed instead. Reichelt, in his funerary suit donning his failed contraption, the armor of his contraption behind his back forming an incidental cross with his spread-out arms, posed as a martyr, Christ-like, transfixed on a nondescript Golgotha, laden with spectators from another failed attempt at “flying” , this time from a biplane, by Gerard Masselin in 1963. At 9×7 feet, we are placed among the spectators, as spectators spectating the spectators spectating the twin fatalities. Spectators with twin cause for awe but leaning towards the morbidity of failure, like the thousands that flock towards the crucifixion site in Pampanga every Good Friday, reveling vicariously in the spilled blood and nailed flesh of proxy Christs. Tatong reduces Reichelt to a shell, his face defaced as a fleshy peeled mask, to reveal no martyrs, no heroes, no romantic Icarus, but mere form, mere compositional element on which to build a picture from.

Sontag (still from Regarding The Pain of Others) delineates the difference between images drawn or images taken as a designation of language : “ Ordinary language fixes the difference between hand-made images like Goya’s and photographs by the convention that artists “make” drawings and paintings while photographers “take” photographs. But the photographic image, even to the extent that it is a trace (not a construction made out of disparate photographic traces), cannot simply be a transparency of something that happened. It is always the image that someone chose; to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude. “

Language or how it is enacted or proceeded upon invariably seeps into how we view images. Tatong’s reconstruction of Reichelt’s and Masselin’s death belie the layers of facsimiles and transmutation of these images – painted and traced from a jpeg file downloaded from a website that has digitally archived their film documentation from a large cache of files made available to the public, intervened further by Tatong’s recomposition and defacement of the figures. It’s realness now exists as a painting, the corporeality resides now in the paint itself, the spectacle transposed to the artistry of its making. The actual historical circumstances of these fallen figures are now eons away.

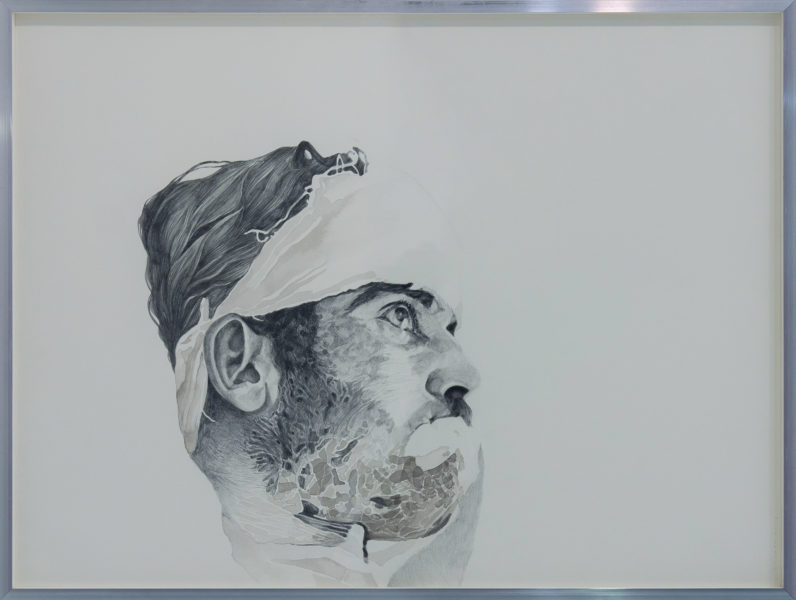

Distancing from the actual event happens by bombardment of images and by construction from disparate photographic traces. Blurring these photographic traces creates a space of wider speculation, where whispered unfounded narratives echo within. Tracing is imprecise as well, especially if sheathed in so much layers. By being plied by sheets of tracing papers, it unsettles the veracity of the events that Tatong has depicted in these two watercolor works. Such treatment has diffused further the pale visage underneath. One is that of Linda Wenzel, a 16 year old German school girl who ran away from her home in Pulsnitz, East Germany to become a Jihadi bride to a Chechen fighter whom she met online who has converted her to Islam and ultimately recruited her to the ISIS. The portrait was a screen capture of a video footage of her ensnarement by Iraqi soldiers in Mosul. Her brows so knitted, her forehead so furrowed, her eyes so downcast, her skin so pale and razed with pink rashes, her hair and clothes so disheveled, hers is a picture of absolute uncertainty – to be meted out capital punishment by beheading by the Iraqi soldiers or to be extradited back to Germany. This may be the last that we see of her or remember of her. In a couple of clicks away, she’ll just be a footnote to a continuing decades long geopolitical and ideological armed conflict, a few clicks further the familiarity dissipates with another trending video clip or meme. It just cycles on to another human interest story that fit the agenda of either side.

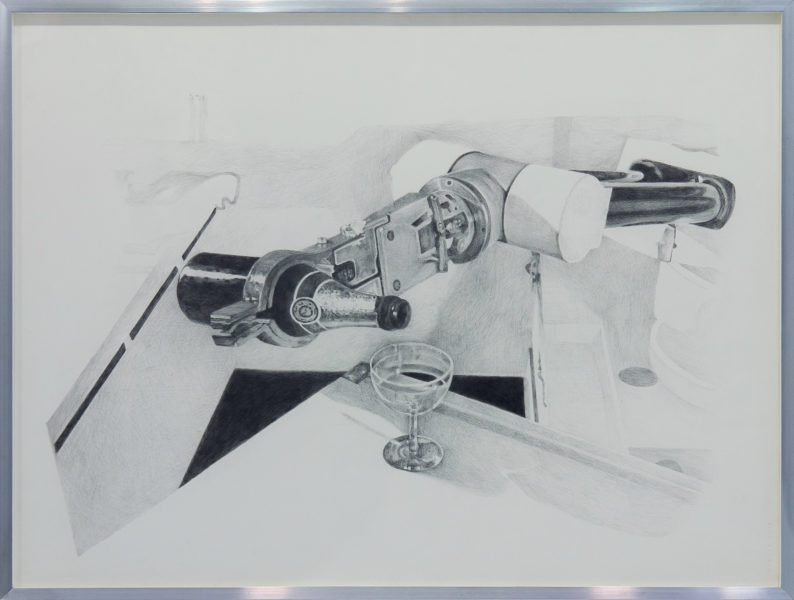

The second image is that of a screen capture of a video footage of an ISIS soldier in black toppling over a statue in a museum they have ransacked in Mosul in June 2014. It was part of their propaganda video in actively vandalizing and destroying vestiges of culture and history that are not in keeping with the Daesh theocracy. To destroy history, is to destroy identity, and hence to destroy the other, total annihilation to those who don’t and won’t belong, wiping the slate clean. The mutilation of inert figures somehow still feel visceral because of its symbolic violence and its implication stated above, their very motive to why they commit such. It’s conceivably far more totalizing in diminishing our humanity with brutal effacement of our symbolic worth than any hacked flesh. It is total erasure of human potential, to reduce man to mere components of DNA and RNA, no different from any other creature. Only if these were actual representations that posses that aura of history. Iraqi museum director Fawzye al-Mahdi claimed that the statues destroyed in the ISIS propaganda videos were merely plaster replicas. The actual Assyrian and Akkadian era statues are still intact, hidden and secured under his care. What does this leave us then? Primarily mortified and relieved after the fact that they are not authentic. Still, the act remains and is looked upon as violent defacement. The “real” now resides in the symbolic, just as much as terrorism conscripts acts at the symbolic. Image becomes language becomes methodology becomes ideology. It obfuscates by layers the half-truths they wield.

“Beauty will be convulsive , or it will not be,” as Andre Breton posits for one of the tenets of surrealism. Sontag repudiates this by the compulsion of consumption, including images, in the complexity of the contemporary image world, underlining the reduced facile servitude of such intent to mere show-and-tell, for “ the image as shock and the image as cliché are two aspects of the same presence.”

In this constant stream of image production and consumption, are we inured already to images of atrocity and death, or do we just ascribe them levels of tolerance and plausibility? Given that discernment should be of utmost importance in viewing them in light of a disturbing Orwellian zeitgeist, viewing them should still feel like drinking liquid drano. Pleasant views are fire in your eyes.

– Lena Cobangbang

Works

PLEASANT 2

PLEASANT 4

PLEASANT 4

PLEASANT 3

PLEASANT 3

PLEASANT 3

Documentation