Speaking in Tongues

I have always seen art as a tool that enabled me to process and react to my immediate environment. It was also a way to examine my intentions and motives.

In previous shows, my process was about spontaneous creation through the act of damage which I had done through a variety of methods such as puncturing, cutting up, shredding, collaging alongside painting until the layers culminated into a figurative form. In my last exhibit, Pulô, I attempted to contain the randomness brought about through weathering from seawater and sand in the city of Capiz, and used this as a starting point for portraits.

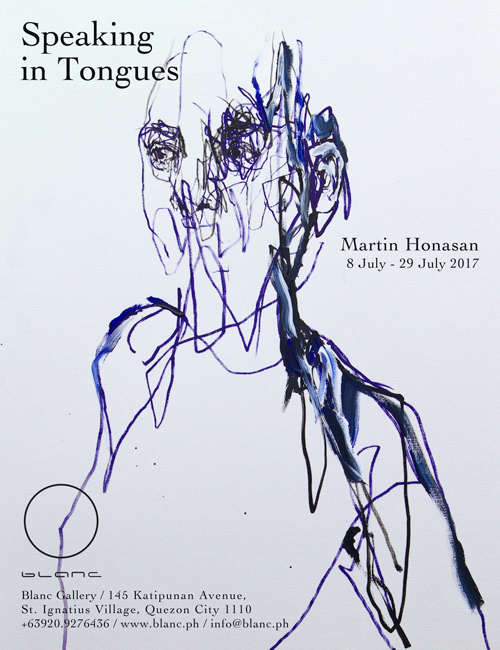

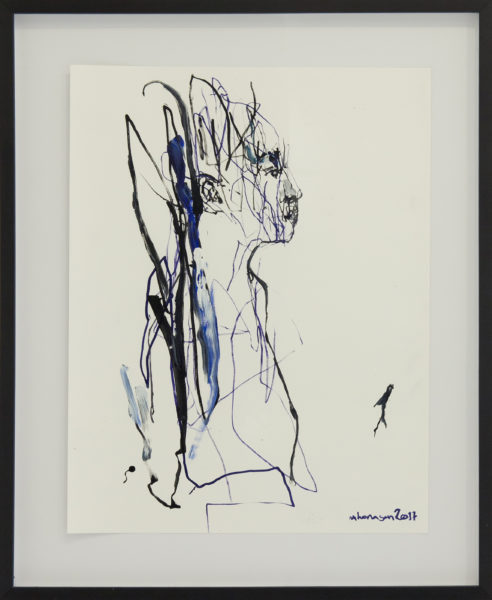

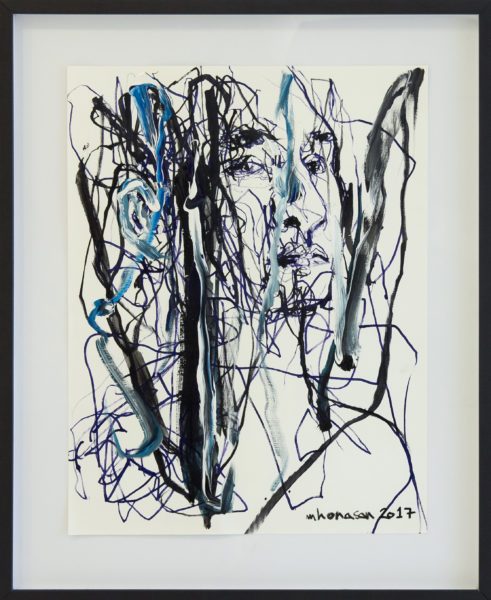

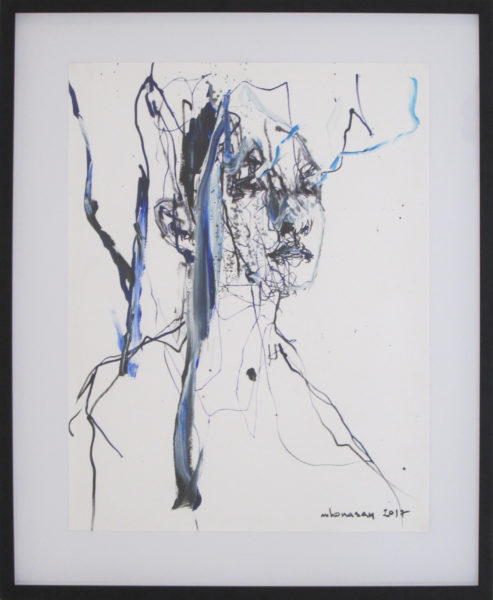

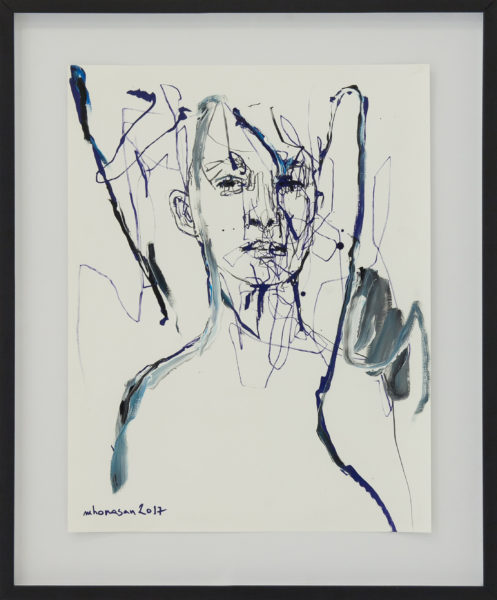

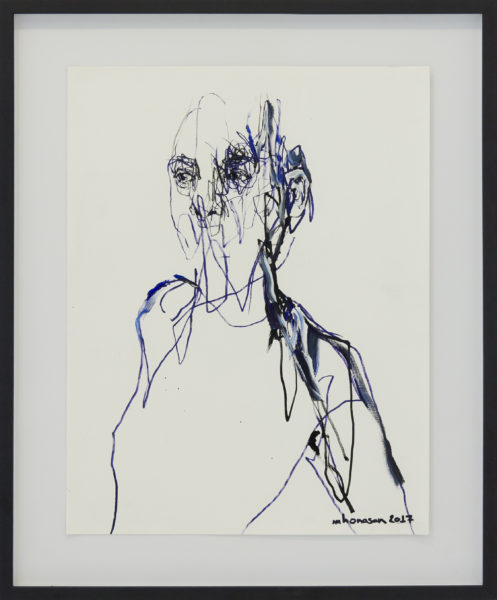

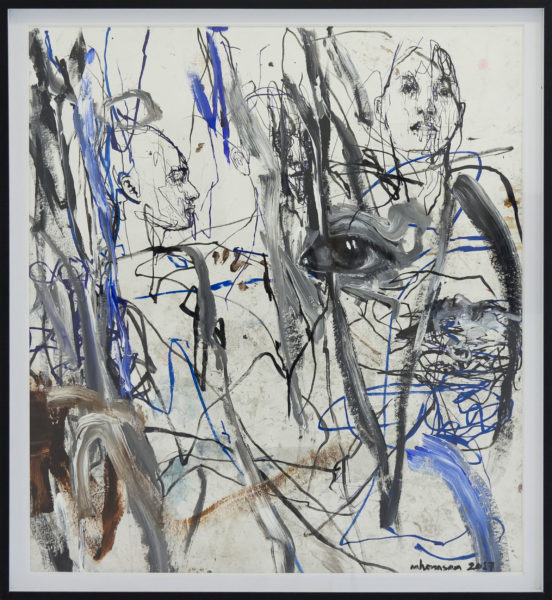

For Speaking in Tongues, I decided to simplify my approach even further by focusing on more linear work––one of many foundational constants in my paintings. With paintings it is generally more difficult to see movement, direction, and intentions due to multiple layers hiding these elements. My goal in this series is to reduce the work into more basic components to highlight what is irreducible, fundamental, and essential to convey meaning. Intuitive calligraphic movement has always been an important aspect of my process, and the flow underneath my paintings has always followed the course of lines: short reluctant dashes, long uninterrupted strokes, or bold and thick impastoes. With linear work, calligraphic elements such as pressure, direction, speed, acceleration, deceleration are clearly seen, making my posture more evident in the pieces.

During the 1st century A.D., in the ancient cosmopolitan city-state of Corinth, a multiethnic Christian congregation, most of whom were Greek, Roman, and Jewish converts miraculously spoke in languages that were previously unknown to them. Well over twenty ethnic groups heard their native tongue spoken with fluency. In some cases the words of the speakers were described as ecstatic utterances, which was said to be the language of the Spirit, intimacy with God himself. Ultimately, it was a sign for believers that the gospel had overcome ethnic, geographical barriers. It was an act of faith, and they were certain that their inarticulate gibberish would be heard as concrete messages.

The arts also offer a similar balance and tension in its communication. A musician who has achieved a certain level of proficiency is said to have a broad musical vocabulary. With fluency, Jazz musicians, for instance, perform at such a high level, they build up tension that is released when the band erupts into formless improvisation while creatively locked in a dialogue of direct commentaries with each other, then miraculously, on cue, return to form. Even in the visual arts, movements such as Surrealist Automatism and Abstract Expressionismhighlight this approach which often emphasized spontaneous, unconscious creation.

In all these froms of expression, from uttering divine mysteries to composing an oeuvre there seems to be an area that straddles the line between having intent and being arbitrary, where purposed intention and random decisions are not mutually exclusive concepts, and erratic movement finds precision––where there is an assurance of what we hope for and certainty in what we cannot see.

Works

Disembodied Mind

After Thought

Untitled 1

Untitled 2

Stoicheia 1 (Series of 6)

Stoicheia 2 (Series of 6)

Stoicheia 3 (Series of 6)

Stoicheia 4 (Series of 6)

Stoicheia 5 (Series of 6)

Stoicheia 6 (Series of 6)

Hills and Valleys

Documentation