Tomb

Temple

Machine

and What Else?

That the “body” may signify very different realities and perceptions of reality. “The body is the tomb of the soul.” – Plato

“Your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost.” – Saint Paul

“The human body may be considered as a machine.” – Descartes

“The body is what I immediately am… I am my body.” – Sartre

That in sum, the body has no intrinsic meaning. Populations create their own meanings, and thus their own bodies.

In this excerpt of Anthony Synnott’s 1992 essay, Tomb,Temple, Machine and Self: A Social Construction of the Body, painter and visual artist Don Bryan Bunag unflinchingly deep dives into and coasts along philosophical reflections on the purpose and meaning of being, and all the attachments that seem to come with having sentience and form: identity, and the interplay of physical, emotional, and social relations that either make or break it. In this solo series of acrylic ink and cotton thread on canvas, Bunag weaves his thoughts freely around the core of certain existential questions: Will our definitions of our attachments really help us finally find and understand the self? Does it bear any weight to understand it, or is it just human condition to be hardwired to seek patterns and meaning in order to make our existence palpable?

While looking for reading materials on prayer in different contexts, he stumbled upon Synnott’s essay and used it as a prompt to explore the urgent reaction the piece stirred within him. Instead of deviating from his original concept, he imagines it branching out into what he imagines to be an interconnected exploration into becoming better acquainted with the idea of being here, now. In this series, he imagines the intangible and vital elements of civilization— knowledge, intuition, and consciousness—take shape from his needle-thread-and-paint visualizations, seemingly arranging and rearranging themselves according to a cosmic, intelligent design that humans might not yet be privy to. Treating sewing as a slow, meditative process—and a sentimental one, where he remembers his grandmother as a dressmaker—he reflects on the very act of stitching with each image he creates. Am I forming the image or destroying it? He thinks, both as creator and observer of how his work materializes according to and beyond the initial blueprint he mapped out, all while reflecting on how physical forms and structures give humans both a sense of being and fulfillment just as easily as they crumble and unravel us as the messy machines of flesh and emotions that we are.

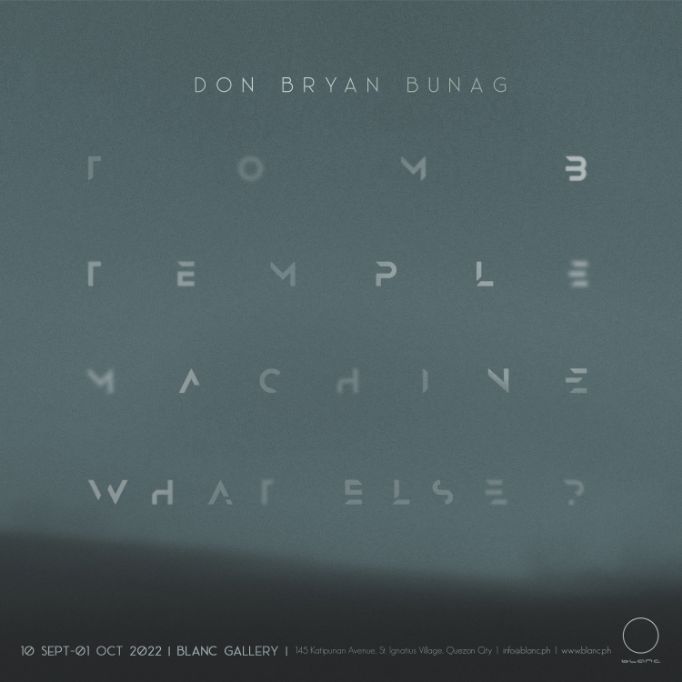

Using the relationship between paint and both the soft, tactile quality and hard, clean lines formed by a single strand of thread, he illustrates elements into existence that appear in one frame, but exist apart, in different dimensions. It is the tension between this incongruence of elements that steers the flow of the artist’s pieces, and also the kind of tension that the artist naturally seeks out during his creative process.

Having grown up in Bulacan, the artist finds his natural drive for certain contrasts—combining the simple and the complex, the analog with the modern—as one deeply rooted in his surroundings. With the province acting as both the geographical gateway to and from northern Luzon and Metro Manila and as a place where nostalgia coexists with modernization, the artist grew up witnessing the flux of contrasts through his province’s gradual urbanization. In his works titled “Theories” “Higher Being”, “Empire” and “Intuition”, we see a combination of the artists’ personal and artistic influences come together, where his brutalism and minimalism influences form cosmic highways over idyllic landscapes that stand as mute witnesses of meaning taking form, and his fascination with physics and architecture play out like visual meditations of his reflections on time and space against the natural scenery of his hometown. While the pieces appear like digital illustrations, a closer look reveals an application of traditional embroidery—which gives the viewer a glimpse into the method behind the artist’s motions. Considering himself to be a slow, deliberate painter, Bunag’s painting process usually involves several layers of color in its initial stages, gradually stripping away certain layers until he arrives at certain shades or tones that he wants to highlight.

Like most, Bunag felt the pandemic’s purging, heightening our sensibilities and awareness of ourselves, pondering on what purpose we serve or does it still even matter to know—with the crowdedness of concerns we face in the age of weaponized information and technology, a tense political climate, and an equally intense actual climate. He would ask himself, at this age that we receive information faster than we can reflect on ourselves, how does this affect us? Would these definitions help us identify our “self” or lead us farther away from our “personal truth”? Should the answers come from external sources or should we look inward? And if ever there really is an answer, is it final or would it raise more questions to be answered?

Tomb, temple, machine—and what else, and then what? How much of ourselves remain when form dissipates? In his 21-piece installation titled “Birth of an Ocean”, scrolls unfurl with hair-like strands of thread, like an ancient and dormant being that doesn’t concern itself with such questions. Like the open sea, the inkling of a mere “what else”, could be what drives a fish out of water. Perhaps it’s the mere idea of a possibility that breathes life into purpose.

-Nikki Ignacio

Works

BIRTH OF AN OCEAN

EMPIRE

HIGHER BEING

INTUITION

THEORIES

Documentation