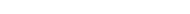

Evidence of existence, painted in 50 shades of gray

Cinereous of skin and woeful in countenance, the subjects of Renato L. Barja Jr.’s Sitting on a Bird’s Back are a far cry from the gods and rulers immortalized in classical portraits. The art of portraiture traditionally belonged to people in power, whose idealized faces reflected their “inner significance.” In this exhibition, Barja flits among paupers instead of princes, documenting them with an ashen palette that matches the cheerlessness of their world. “Society is grotesque, macabre and covered with irony,” he says. “Nothing happens; only the calendar changes. People stay where they are. They shiver. They die.”

Barja insists that he is not a “merchant of misery selling anguish and angst,” neither does he claim to be saint or savior. Instead, he characterizes himself as an observer—hence the title of the show—who wishes to dignify the loners and oddities, the denizens of a glaucous environment choked in concrete dust and floodwater. His paintings and sculptures provide evidence that these people exist: the specificity of their lives are captured in talismans; the pathos of their struggle, handled with respect.

See the grease-stained shirt of Businessman Basilio, whose paunch is the only thing he has left of his better days; the shoeless foot of the uniformed Promodizer, sleeping in her seat and too exhausted to care. Witness the rosary and scapular in Crazy Lady Outside a Local Drugstore in a Deadtown; the jaundiced eyes and stained teeth of Ed the Tombstone Painter; the black mourning pin and keys identifying The Landlord; the rose tattoo on the ankle of Nene the Caretaker. The size of the Nene sculpture is notable; its life-sized treatment shows that Barja is extending the limits of his three-dimensional works, which, prior to Nene stood only about a foot or so in height. Rendered in human scale, her bug eyes and buck teeth become even more disconcerting.

Barja’s subjects possess an unease about themselves—a symptom, perhaps, of their self-awareness. They are not blind to their plight; the tenseness in their demeanor and rigidity of their posture are fitting. How can the Father of Today relax his shoulders when he cradles two children in his weary arms? How can Sylvia La Torre, Beautician for the Corpse mingle among the living without feeling ill-suited to the present? The details in the latter piece are telling: the garish clown makeup hiding sallow skin, the masculine hands with jewel-toned nails, the shoulder pads rescued from a bygone era. Sylvia is an entity out of place and out of time.

Barja inherited his eye for detail from his mother, who pointed out misfits on the street and used them as cautionary tales. The artist has evaded the fate of his subjects but his kinship with them has never faded. Barja knows what it is to be cold and hungry, to be weary and miserable.

Aside from portraits—both painted and sculpted—Sitting on a Bird’s Back includes All Is Well, an oil-on-canvas work that captures the irony Barja spoke of, and Puppylation, a fiberglass-and-epoxy kennel of life-sized dogs. All is Well is a throwback to the rains that changed Barja and soaked his canvases in gloom. A “baby bus,” a common mode of transportation in Barja’s town, is stranded in floodwater. Its windshield placard proclaiming “All is Well” is as jarring as the festive bunting in the background. Installed beneath the painting is a canine family suffering from tick-infested skin—exposed to the elements, raw and pink. The mother, with her sagging teats and bell around her neck, leads the despondent pack to nowhere. Her pups, in various stages of death, trail after her. Barja’s punning title (Puppylation) transforms the wretchedness of these dogs into a comment on the human condition. Their sorry state is ours.

The heaviness of Sitting on a Bird’s Back is mitigated by the naïf style of Barja. Though he is loath to accept it, his work could fall under the category of “cute.” If so, Sianne Ngai’s definition of “cuteness” as an “aestheticization of powerlessness” is appropriate. Barja’s subjects are harmless, unthreatening, emasculated. They are at life’s mercy and they cannot hurt us, although their defeated stares serve as reminders that all may not be well with the world.—ll

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION