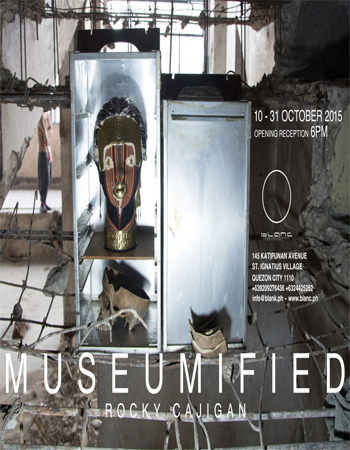

MUSEUMIFIED

“We are what we imagine….Our very existence consists in our imagination of ourselves….The greatest tragedy that can befall us is to go unimagined.”

-N. Scott Momaday, a Kiowa Native American novelist

Rocky Cajigan’s 22 assemblage pieces and sculptures are a pastiche of fragments of individual and collective life. Borgesian visual poetry. Interlinking concentric circles of stories made up of found objects and pseudo artifacts, remnants of Cordillera and colonial cultures that are set within a retable of a larger story. One must read the contents in each shadow box, and the elements of each sculpture, across all of them in totality.

Cajigan’s works command attention to the details of his Bontoc ancestral journey back and forth to a culture that resisted colonization and fetishization for centuries until it could no longer. Yet, the resistance is visible in the contemporary art and literary practices of Baguio-based emergent indigenous contemporary artists and poets, and the thriving schools of living traditions, largely unknown to the nation which pays politically correct lip-service as seen in the caravans of white tourist vans winding up and down newly made and paved roads, affecting the Cordillera ecosystem without a genuine interest in its multi-ethnolinguistic inhabitants and cultures.

Dismantling stereotypes and celebrating differences, Cajigan’s motif is decolonialization—an act of strength instead of weakness found when one unearths, embraces, and pays homage to what has been erased, exoticized, romanticized, rendered taboo, marginalized, and forgotten. Multicultural identities and experiences—Bontoc, Gaddang, Ilocano, Kalinga, Ibaloi, Kankaney, Ifugao, Spanish, American, rural, urban, heterosexual, homosexual, Christian, animist, Hindu—collide and converge in allegorical synergy.

Cajigan is both an investigative ethnographer and archaeologist, reclaiming the past alive in the present—shards of human viagra usa skulls, candelabras, reptile skin, white baby dolls, monkey skulls, heirloom beads, Christian icons intermingle in syncretic mythologies and authenticity. Multi-dimensional realities that resist simplistic responses to What is Filipino? What is indigenous? What is identity? The notion of identity unfolds as a construct subject to change contextually, situationally.

Ironically, the artist asks us to put on worn-out leather shoes laced with human hair, its interior padded with strips of indigenous textile, to conjure up what it feels like to have one’s feet that once walked barefoot chineseviagra-fromchina along rice terrace walls now in bondage. Asian cosmetology lesson heads with human hair, wrapped in Cordillera textiles with brass eyes and lips, peso coin inserted in the mouth with a slave collar with embossed words “Insert Coin To Buy Art” reference notions of beauty, headhunting, the art market, the commodification of indigenous culture, and museology in a tongue-in-cheek manner.

Cajigan asks us to critically think and engage with a gamut of emotions that are perhaps similar to his own when he created each piece with ir/reverence—contemplating the significance of juxtaposing entities and identities in a playful and poignant way.

It would be too easy to fixate on the multitude of hand-carved wooden penises and cutout Biblical pages from an Ilocano translation of the Books of Exodus and Matthew in the shape of a lingam prevalent in many of the works and reduce their meaning to sacred phallus worship reminiscent of Cordillera, Greek, Indian, Nepalese, Indonesian, Bhutanese, and other cultures. This meaning is inherent in these pieces. Yet, their inclusion also allude to sexuality, Spanish and American imperialism, sacrifice, and castration.

The piece Fagan Theocracy 1 embodies these bittersweet ambivalent sentiments. Read: chalice full of penises. A gold-painted Sto. Niño with an erection crowns the body of a 35mm single lens reflex camera whose brand in brass is labeled “Fagan,” which others may pronounce as “Pagan”—“Fag”an against a backdrop of lingams. A genderless white baby doll’s legs are stuck in the camera’s body, restrained by a single thread of Cordillera textile tied around one ankle. Does the thread signify “savior” or is it an expression of saving oneself from the colonizer’s or heterosexual-is-the-norm’s gaze?

The narrative can be interpreted as a tug-of-war with ambiguous faith, cultural memory—the Philippine-American War, benevolent assimilation, canadian pharmacy yahoo and Secretary of Interior Dean Worcester’s infamous photographs of the proud Cordillera peoples immortalized as wild, savage, and uncivilized. Or a clever play on words in which the viewer creates his/her own story depending on his/her life experiences where the person’s positionality of outsider, insider, somewhere in-between plays a role in interpretation. Ultimately, the creator holds the key to its multiplicity of meanings. Empowered.

Each piece in Museumified problematizes representations of indigeneity and defies what one might expect to see in an anthropology museum, critiquing what kinds of objects, art hold value and to whom. There are no mummies here.

Angel Velasco Shaw

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION