Hallow: Nona Garcia at Blanc

The presence of bones, bared or exposed out of their original designation which is within a creature’s flesh, have always occurred to us as signs of morbidity. They remind us of death, of our limited time in this world, and of

what we would eventually leave behind. They outlast us and are the true referents every time we speak of the living and what ‘remains’ in their passing.

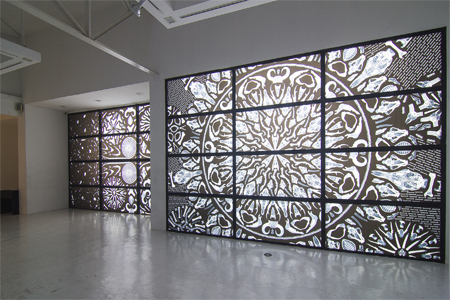

It is also true, that for a prolific artist such as Nona Garcia, the meanings we associate with our concept about bones can be turned into something else, in the same way she has turned our experience of a gallery space into something different: as a massive lightbox where the viewers are enclosed from within. This is the proposition from which her latest show, Hallow, is found: that an immense source of light, which can be projected inside a space, can act as agency for the amplification of artworks, in the same way Cathedrals and sacred structures have used stained-glass designs or Rose and Catherine windows to illuminate the place with art and symbols.

It is an idea found according to the structure of the gallery itself. Blanc Gallery, which features more than forty feet of glass window panels as the façade of its exhibition space, worked perfectly as a virtual absorber of sunlight. From this idea sprung one of many ideas from Nona Garcia’s longstanding explorations in art and her use of X-ray machines. Garcia, who was raised by a family of doctors, traces her affinity with the tool as one of the first remarkable experiences in terms of looking at things differently, and with respect to finding the essences of things within the visible world. Having lived closely within the environment of hospitals and medical laboratories throughout her childhood, the illuminated plates from radiographic images opened up a new ‘visible’ world, together with a new understanding on how reality can otherwise be represented. As an artist who also paints photographic representations of subjects found within actuality’s immediate setting, she has refrained from contenting herself within prescribed notions about representing what is ‘real’ in art, as she continues to explore both the ‘presence’ of the subject in painting (through objects wrapped in cloth or portraits with absent faces) and the underlying reality of familiar objects through the use of X-rays.

Through this method of defamiliarization that Garcia has continually used in representing familiar objects or settings, she, for this show, has opted to use the X-ray machine as a tool in the same way a painter would choose a certain palette—in finding the necessary set of components in order to achieve a certain effect. Deviating from her previous radiography of synthetic items such as relics, tools, or household objects, she has, for this exhibition, elected to pursue the thing that is most associated with the process: skulls and bones from a collection of preserved animals.

The collection of skeletons range from the domestic to the exotic, from wild animals like hyenas, crocodiles, beavers, birds, and deer, to living organisms like corals. The X-rayed surfaces come from different parts: limbs, legs, mandibles, teeth, and horns. These parts are utilized by Garcia as elements in creating a broader composition. Like pieces in a puzzle, each part becomes a necessary component for the bigger picture. Garcia combines them, as if composing an oeuvre, to form an intricate pattern that will re-define the nature of these carcasses that are usually identified with the macabre.

The appearance of skulls and bones, however unsettling it may seem for the living, is part of the same reality. Garcia adjusts to the uneasiness of this fact by treating them as instruments to achieve harmony, symmetry, and balance—qualities that are ascribed to what can be considered as pleasurable. To achieve this, the bizarre characteristics of exposed skeletal structure, hollow eye sockets, ominous jawbones and elongated spines are transformed through the artist’s hands as cold, hard, facts of nature, flirting with the kind of detachment monks and mystics have settled into to ward off emotions encumbered by fear via deathly appearances. The symbol of a mandala is thus placed at the center of this microcosm which Garcia was able to conjure. Like a fractal of galaxy across space or beneath the depth of the ocean, the cluster of matter disperses at each side, before it fades into darkness.

Printed across the whole stretch of the gallery’s backlit windows, Hallow projects a kind of glow the same way radiographic plates are examined across lightboxes. But with this kind of massive spectacle, we are drawn not to the grotesqueness of extinction’s morbidity but with the gloriousness of an achieved unison. The glow redefines the attitudes we have been accustomed to when it comes to looking at X-ray pieces—when we anticipate strangeness, brokenness, disease, or even death. With the projected glow permeating through the outlines of each oddly shaped figures strung together to form a unified pattern, a kind of gloriousness meets and contrasts the darkness of the room, an effect that is more celebratory than menacing, more festive than icy. It is the kind of unison achieved in creating a mandala—where concepts about life and death are viewed together in equal terms. It is where the revealing images of skulls of cows and hyenas, antlers of deer and carabao horns, become part of a greater, consecrated figure—and where the image of the grotesque can find its way into becoming sacred.

-C.L.

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION