Freeze frame. In an instant, a passing scene becomes a particular moment and invades the screen to become the center of our attention, the focal point. The scene is elevated into the ranks of the significant—when once, during a certain point before the pause, it was not even a scene, and was neither the focus for any thought nor the intended stage for any mise-en-scene—that deliberate arrangement of elements inside the frame. The image was nothing but the consequence of time—an inevitable sequence—but time in art has become as elastic as our apprehension of it.

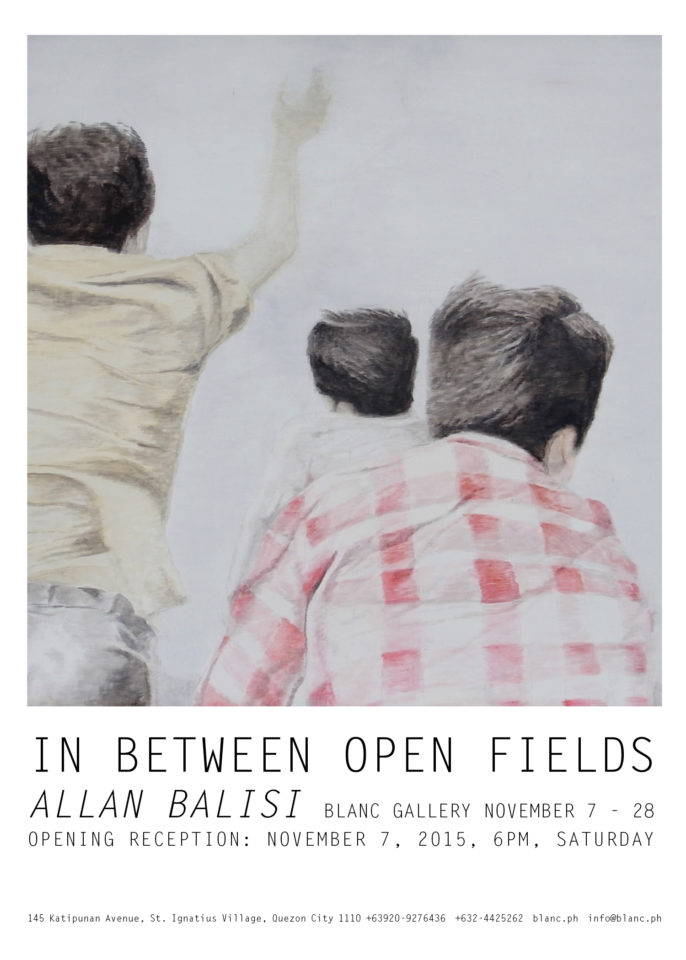

In Allan Balisi’s latest series of paintings for the show In Between Open Fields, he directs his eye to these ‘consequences’ that have entered our attention ever so slightly, like the unheralded and obscure spots between departure and destination. There will always be points A and B to where the narrative develops, where everything in between is happenstance—images that fill the gap of the temporal space. But through that curious event in technology, where we can hold the button, drag the slider, or even start and end at any point within the movie’s storyline, the occupying interstices between frames no longer function as impromptu fillers; and no longer require us to become captivated audiences, in the same manner Walter Benjamin first described the nature of cinema as an unstoppable force of continuous, flickering images that lock us in anticipation towards the next scene. 1 The new way of seeing and apprehending cinema is one of control, where we have become free to roam its ‘in-between-ness,’ and acquire or appropriate its fragments like they were illuminations of a hidden view or clues to an untapped consciousness. This is where Allan Balisi begins his project—in excavating the vast signs that are found in between narratives. It is the vista where he begins to paint—the peripheral, the ambiguous, and the disjointed.

He presents his work using the sparsest of effects: thinly applied paint, with light and subdued hues, and an economy of space along with a resistance to flooded symbolisms. They have become in painting the near equivalent of a film celluloid’s ghostly and translucent quality. It is, after all, the condition of our visual landscape which he would like to capture: the spectral, the undefinable, and the ambiguous. In his work called ‘Splashed Softly Against the Wall and Kiss Them With Love,’ we see a view of a house’s interior, with a section that is broken down—a corner with an opening against the wall, marked by debris unfolding through a door that is undoubtedly unhinged, leaning from a portion of a wall that is partially falling off, showing the layer of wooden armature that has started to come loose. The interior’s quality harks back to a period where television sets are still conceived as wooden boxes. It is a scene from a past—but who’s past? The whitewashed condition of the scene purports this past-ness, which signifies the symptom of fading photographs, of old prints whose images are made visible through the delicateness of light exposures.

Like in most of Balisi’s paintings, color is restricted to a certain scheme—a scheme that, more than anything else, attempts to announce its absence. But the meagerness is a carefully calculated application, involving an acuity for the characteristics of under-saturated and over-exposed photographs. This almost reductive approach to color is not a negation, though, of the potentially powerful effect of hue in painting. It ascribes to what auteurs like Sergei Eisenstein had to say about color, that it only begins “where it no longer corresponds to natural colorization.” 2 What is unnatural about Allan Balisi’s color scheme is the sensitivity it seems to suggest, not through the painter’s palette, but to the effects of light, particularly the light that transforms photo-based prints.

In ‘Words, Words…How Could Easily Destroy Men,’ there is an overwhelming source of light that radiates from above, enveloping the whole scene, which adds to the ambiguity of the action. We see three characters involved in a kind of scuffle concerning items that represent books and other types of paper being hurled up in the air. The saturation of light becomes more apparent at the top of the frame, as the white pages of these floating items begin to blend with the stark, white wall that is almost void of texture. The details of the painting seem to rest below the composition which include vertical, black and white lines that make up the pattern for a kind of fabric, complimented by the patches of black hair that serve as the only identifier for each character. In ‘Approaching Light,’ the light source is more apparent, which is a direct rendering of an emanating glare—diffused and abstracted, like an image that has gone through the scope of a camera lens. The imagery is ambiguous, without any direct reference to what the subject is except that it emits a powerful lamp, and this kind of understanding that we place towards the scene is the sort of language that can only be possible with our familiarity with photo-based media like pictures and films, to which we encounter these types of rendering.

It should be safe to say that Balisi’s works ascribe to an effect that can only be possible with the advent of film and photographs. An effect that has been adapted in digital composition to evoke a sense of nostalgia—in sepia and saturated tones, transforming the picture through a tap of a button, as if saying that the retro-style is a style committed with absence: the whitewashed, overexposed, and monochromatic rendition of worlds.

But Balisi’s style in painting is not only committed to a past technological effect, it is deeply embedded in the new landscape technology has brought to our senses. The ‘screen capture,’ which is a fairly new technique, at least with regards to the now expansive history of video and film, has become something of a domesticated idea–convenient as most households are equipped with computers and gadgets with digital capacity. It has started to demonstrate a certain tendency, seeping into our collective consciousness, probably in the same way we are inclined to bring our cameras whenever we would find ourselves in momentous occasions. Mind’s registry is no longer occupied by images from natural landscape or real-life experiences, as works like Balisi’s would prove. The mind’s registry for images has now been interspersed with the full range of archived media—films, old photographs, print media, internet sites, and streaming video.

In trying to understand the nature of ‘film stills,’ Roland Barthes once remarked that the still neither has an obvious nor obtuse meaning.3 It is neither the past nor the future, yet at the same time is the only image produced that is definitely part of a sequence that has a before and after. It is not merely a fragment but the inside of a fragment. In other words, the film still can always generate a meaning of its own. The screen capture, on the other hand, which is much more arbitrary and actually more encompassing as it can include every frame of the moving image that can be subjected to a halt, can hold more possibilities for generating meaning. Because during a screen capture, there is no guaranteed central subject, and no guaranteed action or gesture, as well as no guaranteed order in its composition. Everything becomes ambiguous, especially when it is snatched out of the film’s context, as how Allan Balisi would describe his works:

“Using screen-capture, mostly with low-resolution, drive-in movies, I purposely attenuate the colors, making things unclear and imprecise, presenting more inconsistencies. They leave more room for interpretation. [And] I prefer to combine images from manifestly different contexts, to alter meaning by filtering them, cropping them as a painting can be cropped, and eventually reconstructing them with painterly conditions.”4

In one of his paintings, entitled “Vasts Apart,” we are treated into a subject that is placed out of its proper context—it could be part of an obscure movie’s scene, or simply a rendering through the artist’s own imagination: a boy in gloves looking through his binoculars. At any rate, it is an image whose subject has been erased. There is no identifiable expression in the boy’s face, as any possible feature we can trace to his character is absent and is merely channeled through this lone, voyeuristic instrument—the pair of binoculars. It becomes the substitute for the eye—the window into one’s soul. And as an underlying motif in Balisi’s paintings, every character seems to fall into the ranks of the anonymous.

Not only characters fall into the sphere of anonymity but also places. In a painting entitled ‘Standing Still,’ we see an unperturbed view of a building’s façade. The building, whose architecture is unmistakably modernist, is adapted in Balisi’s painting as pure geometric form, giving emphasis to the vertical lines of its construction and the rectangular patterns of dark mass that serve as glass doors and windows. Because of the image’s neutrality, the painting becomes an exercise in form, almost embodying the same modernist stance of the architecture. A lone item—a wiry flagpole with an almost imperceptible white flag—provides the painting its only sign of life. The same goes with another painting of an obscure interior called ‘Tendencies.’ In it, Balisi seems to have found the most generic and banal of all views. So banal that the whole scene is able to devoid itself of any meaning. In this painting, everything seems to count as peripheral view: the white wall, the couch, the opening to a hallway, the floor, a couple of indistinguishable portraits and paintings which are hung. If most of Balisi’s paintings have tried to eradicate any of its original meanings, this, on the other hand, has eradicated any of its possible subject matter.

In his series of paintings that correspond to the title, ‘In Between Open Fields,’ the whole notion of images placed out of their original context is catapulted into three separate paintings. The close-up view of hands holding each other demonstrates a momentous crop, from its original sequence and its original context. Without any trace of preceding or following an action, we are left with this unusual gesture that begs for any symbolic logic. Another is the image of boys who seem to have found themselves facing an empty field. Again, the gesture remains a mystery—the vast open sky in front of them denotes the possibilities of meanings. Thirdly, is an image of a car crash, which constitutes for a whole lot of prior action before it could have possibly reached its state. But as Balisi’s project demonstrates, all of these images’ sequences are ‘abandoned,’ ‘discarded.’ The specifics of past and future are gone and we are left to take them as for what they are—as fragments, or, in echoing Barthes’ description of film stills: as the inside of fragments.

Whether from discarded old photographs (like ‘Leaving Stones Unturned’) or fragments from obscure movies (Denied by the Clocks That Tick at Us at Every Side; I’ll Give up It’s Okay), the works of Alan Balisi is inscribed with challenges: both that of a continuous search for meaning and a continuous rejection of any definitive significance. In these paintings, the subjects that are painted seem to ascribe to their own disappearances; while the actions that take place within the scene appear to only dissolve into ambiguity. These are paintings that extract that ghosts in the image-generating machines of our culture—photographs, internet, video, and film. Vague, restrained, and translucent; the series strips itself off of any attention-grabbing qualities we have become accustomed to in an age of relentless image-sourcing and of popularities validated according to the number of views. In Allan Balisi’s peripheral scenes, the more they slide past our consciousness, the more triumphant painting has become. (Cocoy Lumbao)

Notes:

1 Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, from Illuminations (ed. by

Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, New York. 1968).

2 Sergei Eisenstein quoted by Roland Barthes, The Third Meaning, from A Barthes Reader (ed. by Susan

Sontag, Hill and Wang, New York. 1991).

3 Roland Barthes, The Third Meaning, from A Barthes Reader (ed. by Susan Sontag, Hill and Wang, New

York. 1991).

4 Allan Balisi, e-mail notes and artist’s statement sent to the author (Dated October 13, 2015).

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION