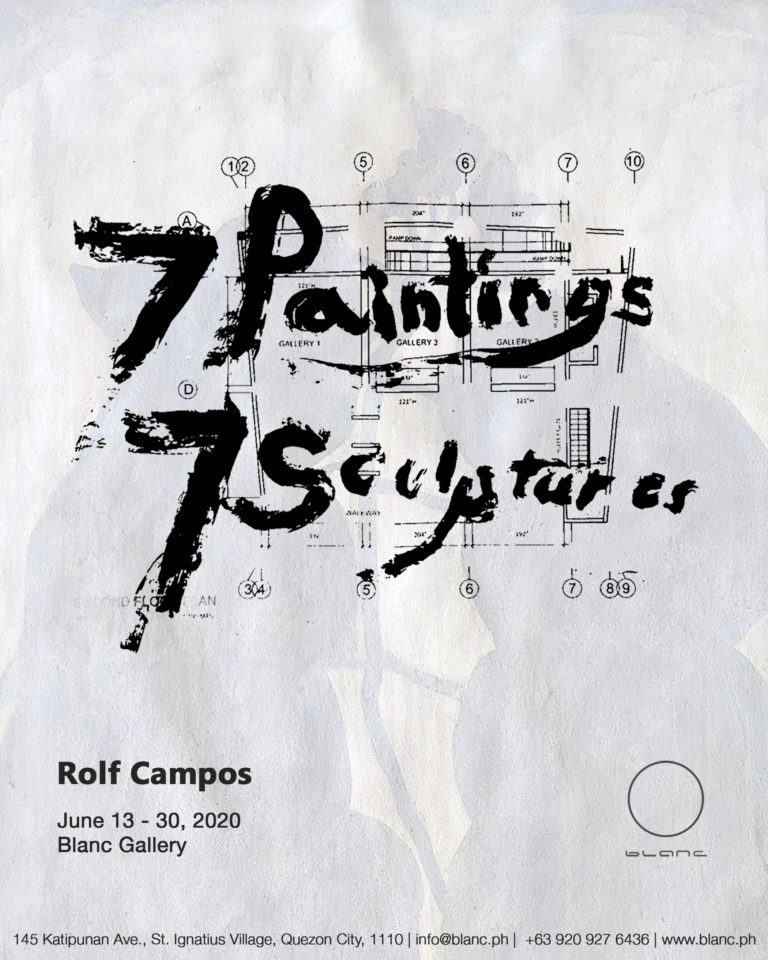

Seven Paintings, Seven Sculptures

Seven Paintings, Seven Sculptures begins with asking questions about old knowledge: where do habits come from? How does formula endure?

Produced midway through the Community Quarantine but conceived almost two years prior — the exhibition, more specifically, began with a preoccupation with belief and time. A palliative and cure for many ailments, the pito pito tea enjoys a popularity so prevailing as to spur commercial, patented formulations. Considered as oral tradition the pito pito recipe births multiple, storied routes extending across islands and groups of people. It is easily adaptable and because the mixture is often made-to-measure it can be highly personal, license nothwithstanding. The ingredients vary not only in number— sometimes exceeding seven—but also in composition, as matter of preference or necessity as substitutes are permissible. The pito pito’s everyday plants and trees feature in many epics, myths, and songs. Seven, of course, is a number which holds significance in many contexts both secular and sacred.

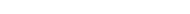

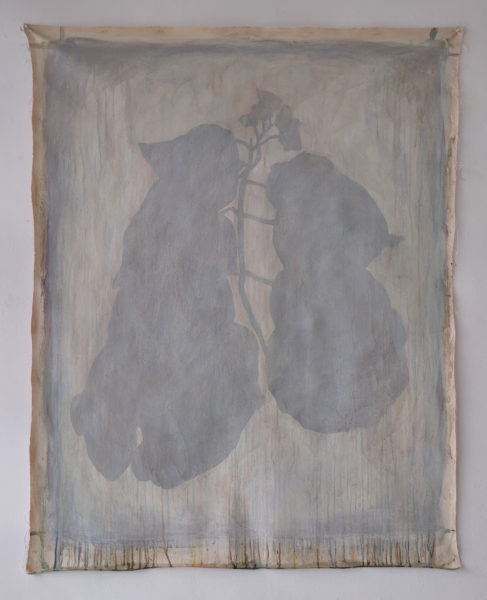

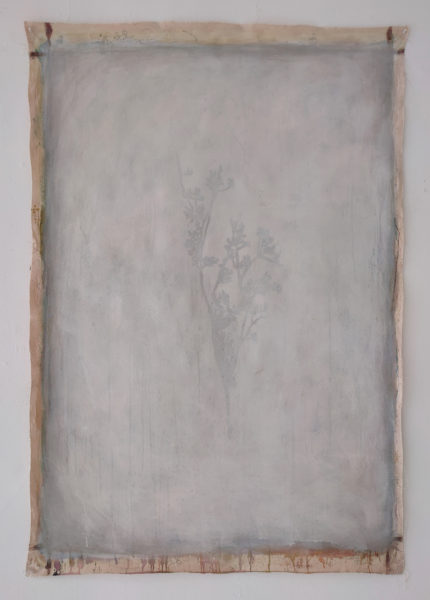

As in the artists previous work, images in the exhibition are taken from herbarium specimens from the early 20th century to the more recent past. These specimens were once collected by botanists in the field to document plant forms within a prescribed region or area of research. Herbaria and its specimens, instructively, were made in the archipelago and nearby islands through the fastidious work of colonial botanists and foresters. Specimens are composed of dried leaves, stems, flowers and small fruits or seeds carefully arranged in the middle of cardboards, positioned and pressed to present the best views of a plant’s morphology. Aside from the dried plant itself, the most crucial information on the collected sample is handwritten on the lower right area of the loose sheet. Herbarium-related stamps, seals, and other identificatory and official markings furnish the rest of the specimen.

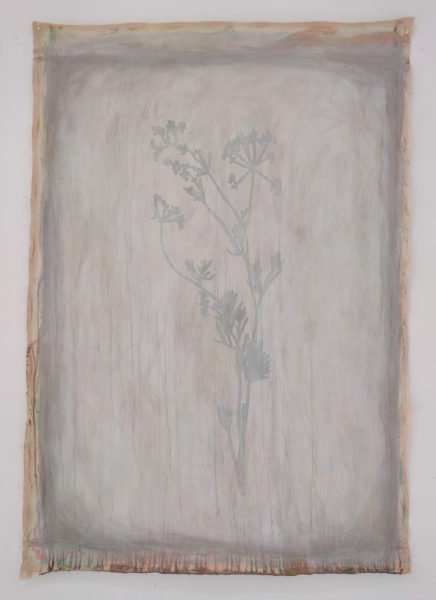

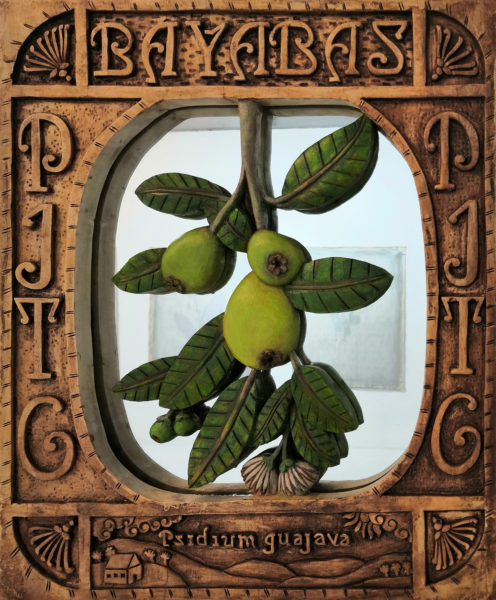

It is important to review the specimen as form and archival material against viewing the paintings in the exhibition. The latter consciously erases all detail and data and instead fixates on nothing else but the dried flora floating in the middle of the cardboard. The images are the ingredients of the pitopito tea: mango, bayabas, banaba, alagao, pandan, gotu kola and cilantro. Rendering even more lifeless an already lifeless form, multiple thin layers of drips and washes of acrylic progressively obscure the plant in a membraneous, milky cloud of paint. A clue as to how they were made is signalled by the ends of the canvas left loose and frayed where a stretcher or a frame would have concealed them. Moving across several houses and locations, the making of these paintings happened across spaces, often by setting up a small “studio-on-the-go” with a box of paints and brushes, a staple gun, and a ¾ inch sheet of plywood serving as the artist’s easel. The paintings are left in the same condition they were in from the artist’s various places of production— other people’s living rooms, corridors, offices and backyards— an intimation of the often peripatetic and precarious work of artmaking.

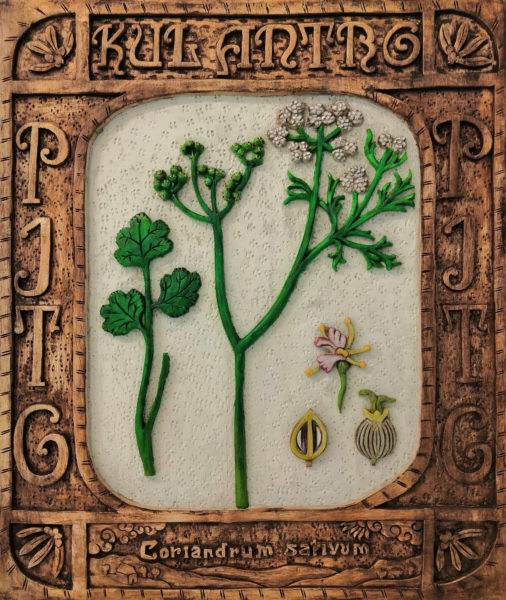

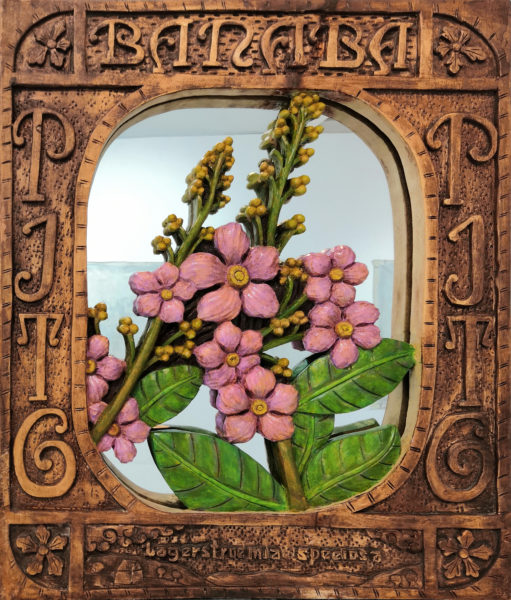

Echoing the paintings are seven relief sculptures executed by woodcarvers from Betis, Pampanga. The artist likens the process of creating the bas relief sculptures to his own process of painting, that is foregrounding intuition and keeping the work of the hand visible. From painting the watercolor studies for the woodcarvers, to the actual method of carving, and finally back to painting and staining the wood, there is a primacy given to the hand-drawn and the hand-cut. Some of the reliefs have mirrors allowing the viewer to, according to the artist “see oneself among plants”, an invitation to establish one’s relationship with plant life through one’s reflection. Above all, the sculptures are forms of memorialisation. The seven plants are made deathless in the same way that the Via Crucis immortalizes (and almost always in small wooden relief tablets) icons, symbols, and scenes related to the crucifixion of Christ.

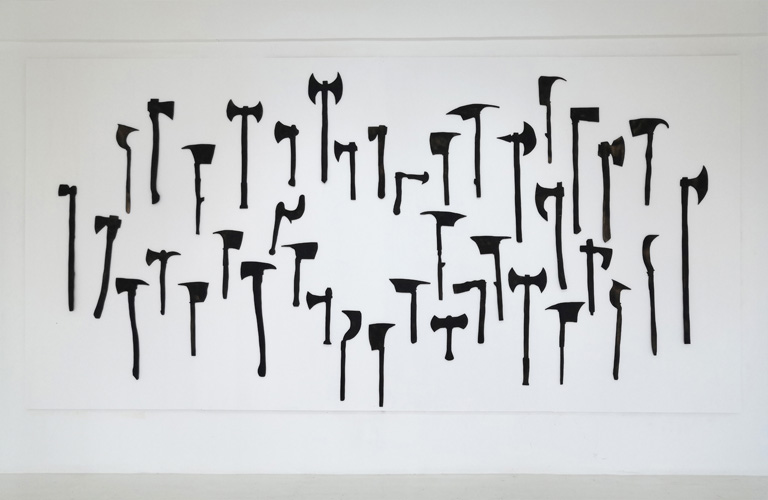

Finally, there are the wooden cut-outs of axes which sit beside the fine woodwork of the plant reliefs. An allusion to the plywood-easel the artist used as his “studio”, the plywood axes are a repetition of the axe-form which, as the joke goes, also forms the number 7 in shape (“puro palakol”) an attribute which the artist repeats over and over materialising into over forty silhouettes of axes from various weapon-making cultures and geological times.

The exhibition now unexpectedly opens in the midst (still) of quarantine in Metro Manila where anxieties over health, unemployment, food insecurity and, ultimately, repressive powers loom. The proximity between death and life, art’s enduring preoccupations, are no longer sheathed in metaphor or softened by the language of symbols.

The artist recalls how in the past two months he has been living with and listening to the elderly (and stories of their elders) while working on exhibition— how they say that the pito-pito is nutritious and comforting, and how during and after the war there was no coffee as there were no producers, no stock, and therefore, no inventory; people were hungry and there was little, and this little was barely enough. During that time, however, there was tea.

Works

Documentation