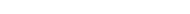

horse

The horse, as an awe-inspiring figure that widely symbolizes the noblest of all virtues such as beauty, strength, grandeur, resilience, power and prosperity, is a prominent artifact of our culture that it has become a sign in itself which immediately communicates its own relations. As a pure object of the known world it is the embodiment of physical soundness, of a potent design and flawless functionality, that leaves it perfect as it is in its straightforward representation. When its context is moved in more abstract terms such as in religions and myth, it is a symbol of wealth, of grace, and of luck. While in its more adverse connotations it provides us images of the dark horse, the workhorse, and the enslaved and furthermore as a pun—whores and the carnal inferences of its vigorous flesh. With the accepted associations on the idea of the horse, it has become a powerful motif both in art and in society itself. It has become a formula for those who have sought after its virtues or its vices.

In an exhibition that pays tribute to the vast associations of the Horse, six artists draw from the array of meanings that can be found on such iconography, and takes advantage of the widespread notion of its acceptance as a positive sign for the times. In a show that is directly named after the creature, without much pretense, the campaign seems too credulous, enough to make us suspicious—is it a deliberate strategy to imbibe within their works the appeal and charm of such symbol, or is it a mock representation of how such motif is exploited within the landscape of painting and sculpture? At any rate, the theme of the show becomes the starting point for each artist’s ideas, and its virtue lies on the gallant application of such hackneyed formula to use it as a means for expressing their sentiments about beauty, personal experiences, and their own motivations for making art.

Beginning with Tanya Villanueva’s painting, I Dreamt of a Horse With a Tear in His Eye, What Does it Mean?, which invokes the power of the horse’s myth and how it pervades our psyche. The image is an illusion which juxtaposes a body part—the flesh of the thigh and buttocks, with that of a face of a woman in tears. It harbors a dreamscape, with the elements floating against the muddle of a dark firmament and bright adornments. It is a pastiche of the art that runs wild within the thoroughbreds of the city’s streets, the Manila jeepneys, the urban workhorses that seem to also portray, through their chassis, the sensual and surreal plights of their dreaming and fantasy. In another work of Villanueva called D.I.Y. (HORSE), a parody is again performed after the once popularized anal plug of ponytail extensions. It is another fantasy that beguiles the activity of ‘play.’ In this work, she employs found household objects instead, reinforcing the makeshift fantasy borne out of limited resources and undermines the superficiality of art as—on the exterior—can be as distracting as a colorful tail that can impede its function on the inside.

In the same manner of showing art’s superficial nature, Lou Lim applies the horse as a symbol of beauty in the work Excess on the Ass, and takes a part of its body, which is the tail, to reflect on our need to compensate for the ideal ‘look’ by using synthetic wigs instead. It puts together what she believes as an enhancer of forms for a woman’s beauty: the shapely buttocks and the artificial hair. And while this explores the horse as a symbol for beauty, her other work, I Make My Own Luck, ponders on the horse as a symbol for luck. But for Lim, luck resonates differently against our common notion. What she takes after is the horse’s hooves and human feet, sculpted in resin and enclosed in glass pyramids. It is for her, more of a testament to one’s submission to hard labor. It is for her, that immense display of power—power that can bring luck.

Luck is also the concept behind Gail Vicente’s works of wax shaped as pyramids. The shape, which is believed to be sacred and constitutes as a ‘lucky charm,’ is inscribed with phrases that resemble a series of epitaphs: “every filly has its day” and “in memory of my money,” which are idioms that can refer to a life lived by a horse/whore. This symbolic relation, through its pun, for her indirectly commemorates the living conditions of the artist, who, as toshiba web cam center workhorses or whores, are always subject to compromise within what the market demands.

Marija Vicente, on the other hand, takes this concept of art as commodity abrasively and head on with her painting titled as Horsex. Its image is as clear as day—horses having sex, its message is as blunt as its image: horses

are lucky, paintings have value, and sex sells. If it is what it is, then the artist has succeeded in copulating the two disparate concepts of form and function. If it is a satirical blow on the methods of art production, on the concept of luck, and the symbol of beauty, then such work is as contrived as it is subversive, like the depiction of the stud’s genitalia, a vulgar operation beneath the surface’s charms.

In Jacyn Esquillon’s works, we are faced with a more personal account

of what the horse symbolizes for her. She gathers memories from her childhood experiences, and relates the horse as a child’s companion, depicting the same sentiment through portraits, photographs, and moving images of women, of the several housemaids that has come and gone in her life. It carries the emotion ascribed to the animal as a creature of nostalgia, of companionship, and of inevitably running away to become free again.

And in Mara Red’s paintings and objects, we look at the horse once again dating ads as a motif, as an aesthetic element and as a conventional subject. In her painting Coltpixie Carousel, she fills her canvas with eight horses which correspond to a number that can bring luck. Its arbitrariness almost espouses the horse as a decorative, as pure as a given shape within a pattern. The horse’s concept becomes as basic as a single expression among her dioramas where they are placed as a recurring theme. Through her, horse takes its place as part of popular culture, a novelty and nothing else.

With these six artists re-claiming the position of the horse as one of the most symbolic of natural figures, we are invited to re-consider as well our own inklings and fetishes about the subject and its pull towards its more prominent meanings. The show gives us a chance to reflect on two systems that are seemingly at work here: the system of art, its method as expression; and the system of the commodity, the value of an object produced for a certain demand. The artists involved in the show openly embrace the idea of the horse as a commoditized theme. But as they play around the prospect of selling lucky charms and feng shui material and are conscious about the demands of http://fromanativeson.com/jav-web-cam-chat-qz4/ selling art, they can also be strongly identified with the horse’s resiliency as a worker, as they all fall under the category of blue-collar artists, seeking both the demands of their vision and their day-to-day needs. sugar daddy online dating In this respect, they might argue that what lies behind the horse’s luck is hard work, behind its beauty an enslavement, behind its magnificence is any meaning we wish to place in it.

Cocoy Lumbao

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION