Everything In-Between

by Jonathan Olazo

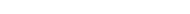

Comprised of four subjects and executed in large-scale murals painted with oil on canvas, In–Betweenness marks the introspective and philosophical turn in the oeuvre of artist Pardo de Leon. In–Betweenness refers to that subliminal, extant place in between any given couple of opposites—in the artist’s texts, “the space between two fingers, or the vast distance to the moon.” By using pictorial devices in the manipulation of perceived space and suggestive symbolic forms in connotative colors, the works are moved into a mode of mediation that thrives in the arena of advocacy for a higher realization, and asks questions about the bigger picture.

In almost all of the paintings on hand, a composite figure of delicately hand-painted parallel and perpendicular lines is made to dominate all over the painting’s respective image. In the emerald green triptych “Forest Kites,” the diagrammatic lines suggest an architectural, monolithic structure—or is it a labyrinthine abyss?—but its end lines falsely dissolve into the painting’s background, and abruptly subvert its logical, suggested shape.

In “The Crack, the Gap, the Alleyway,” de Leon appropriated a formulaic distribution of lines (acknowledged as the Hilbert Curve) in filling up an entire image, covering the surface without having to step over another line, or in this case, its own line which continues on from its point of origination. The image underneath is a masterfully painted picture of rock formations—perhaps indicative of the beautiful power of nature to erode natural formations and a chronicle for the essence of the passage of time. The appropriation of the said systemic device is deliberate, and reveals a personal directive to move the ideal of painting to cross over and cover other various disciplines. (Artistic work can be based on factualness and goal-motivated directives, thus, opening up exclusive platforms that only promote end games for a few.)

In both thematic paintings, “Forest Kites” and “The Crack, the Gap, the Alleyway,” the artist looks to disrupt the perception of normal perspective in her employment of linear patterns: “The lines are just a play on perspective, so you never really know where you are, what’s real or unreal.”

In “Room of Three Suns,” the philosophical bend takes on a different angle. Lines are drawn into heliocentric trajectories and superimposed on a painted figure of a gigantic, glistening globe. (The painted surface of these paintings are beautifully painted one dab of pigment at a time, in de Leon’s signature panache. Her application is loaded with intelligence evoking a mix between Manet’s detachment and Jasper Johns’ premeditated, wayward feel.) Floating with the patterns of heliocentricity are mystical orbs and gemstones. These, along with the globular figure, are allusions to the sun and its essential habitation in every human being.

In the diptych “Round the Bend,” graphic circles are superimposed on a marvelously painted image of a green terrain that inevitably resembles maze-like formations. De Leon has pointed out in her notes that “in some cultures, the circle symbolizes the soul.” In a revelatory bit, she took note of how the circle images were the first to be painted on the canvas before the rest of the painting was worked on, and how she had to scratch already completed parts for these painted circles to shine through. In a very loose connection, the procedure of the palimpsest (layer upon layer of erased and consolidated writing and images) comes to mind, and serves to complement the employment of simultaneous perspectives the artist has called on for her work’s intentions. The painted double-image of traversing hills and valleys ingenuously makes use of the diptych format and illustrates in the mind’s eye: is it the same image repeated? But at one fleeting moment, do the peaks’ curving meet and continue to each other?

Much predicated in de Leon’s writings and quoted notes, it confirms the alignment of current work with the sublime and the spiritual. These are models that make manifest reflections about that metaphorical utopia—a map or diagram for truer aspirations that are usually buried by urgent things that keep everyone at bay and astray. In a likely second-guess, de Leon took note of this dilemma and wrote it down in a moving verse: “the space between coming and going, the notion that everything is in flux, of obsessing between the past and the future…does the present ever hold still?” It gives an answer to what Jorge Luis Borges said: “There is no need to build a labyrinth when the

entire universe is one.”

The artist dedicates this show to her parents Antonio A. de Leon and Elinor Pardo de Leon.

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION