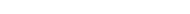

A solitary retreat

If in his earlier exhibitions Kim Hamilton Sulit drew heavily from personal experiences, in his fifth solo exhibition the more pensive artist draws back from these and steps into his thoughts as a man alone in the world.

In the central wall is a monochromatic rework of Albert Durer’s Adam and Eve. A panel is added between the two portraits in which man and woman engage in the act that, again and again across all generations of sinners that followed the first, causes their disintegration. In presenting the copulation of humanity’s parents as a ghostly apparition, the artist questions the idea of sin as perhaps being more illusory than “real.” Like ghosts, it persists in haunting the guilty.

But sex and death are not unreal, as shown in For the love of misery and mystery. Here, forms of men and women wrestle with those of the opposite sex or crows. Naked, they are easy prey not to angels of redemption but to harbingers of struggle and suffering. Savage plot continues the story with a portrayal of man and woman lying helpless and defeated, protected by nothing but their own freakish corpulence.

In depths of the aftermath recalls Dante’s Inferno and neatly arranges the future, present, and past into

an integrated whole. While the middle panel depicts a man sitting in a relaxed manner, perhaps mulling over his hellish past, the future portrayed in the topmost panel is dark and uncertain. This uncertainty is further given context in Like a sleepwalker through the universe of grief, in which three crows and a dissolving baby signify, according to the artist, the presence of death and hopelessness anywhere in the country today. The times are such that even an artist thinking his own thoughts in his quiet studio is enveloped by the tension and anxiety that hover above the poverty and senseless killings that thrive outside. The sense of indeterminacy is also felt in Within the absence of reason which shows soldiers at rest, waiting for orders. Awaiting not so much the certainty of death but an idea of how death will happen, the men’s bodies are stiff even if they are in a comfortable position. The perspective in the painting draws the viewer into the same space where the soldiers sit and wait.

In times of solitude as an exhibition explores one person’s thoughts in twos or threes. In the diptychs and triptychs, a man is placed opposite a woman; flesh has a counterpart representation in skulls and bones; the uncontrollable future and past are balanced, linked, by the present. At the same time, the idea of solitude is defined or made possible by ideas of belongingness: to each other, to one’s family (as in Ripples and Reflection, which represents the artist with his siblings), and to the land one finds himself thrust into in this earth, by Original Sin if it is as they say.

In the middle of the gallery is an installation of a burnt, armless man standing amidst tiny skulls, his disfigurement threatening to tumble him to the ground if he takes one step. The overall form of the sculpture evokes the tragic fate of the last of the Buendía family’s line in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One hundred years of solitude: “a dry and bloated bag of skin that all the ants in the world were dragging toward their holes along the stone path in the garden.” From where I stand provides a vantage point from which the artist reflects on myth and history and literature and their enduring theme: death is the beginning and end of all things but time. From where the viewer stands, she is presented a space like Macondo, a city of mirrors where the only thing constant is history repeating itself. To race against time is to race against death, and anyone who wishes to do so has no one but himself or herself to, like Colonel Aureliano Buendía, try to decode a prewritten — predetermined — manuscript of one’s story. And even knowing the story does not assure victory of any kind, certainly not victory over death, because stories do not stop the passage of time, but do the exact opposite.

-Faye Cura

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION