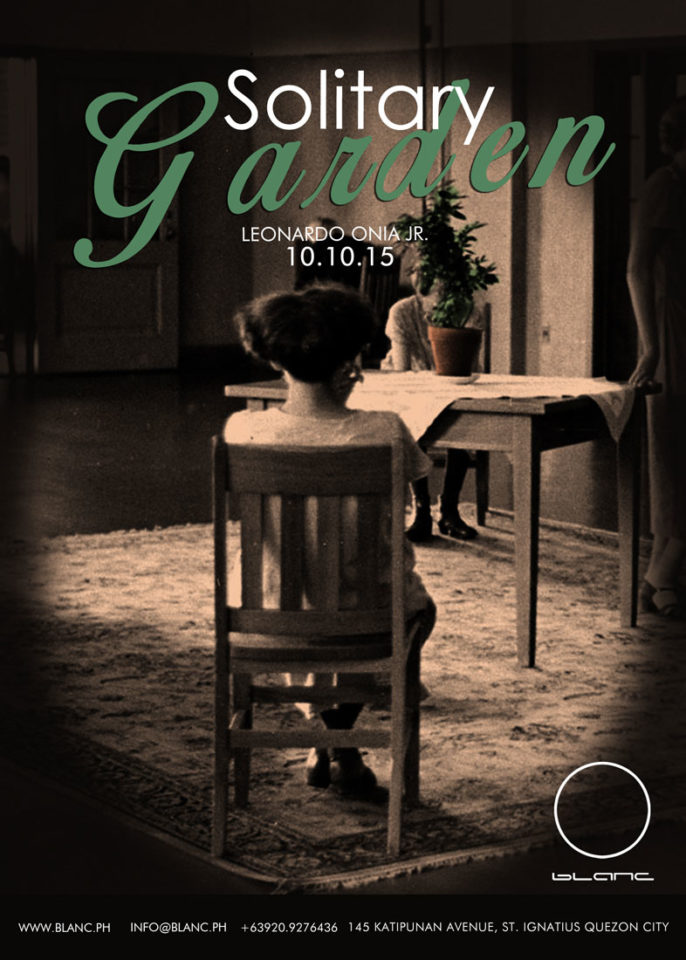

Solitary Garden by Leonardo Onia Jr. is a multisensory descent into madness. Through installations and paintings, he presents a Hitchcockian nightmare of headless human beings who have literally and figuratively lost their minds. Suicide cases lie still on the floor or hang from the ceiling. Mentally ill patients live out their days straitjacketed or bound to their hospital beds, their incoherent inner lives limned by an experimental vocal piece by John Zorn* which bounces between manic, skittering gibberish, piercing screams, and a bizarre chorus of human sounds.

Well acquainted with personal tragedies that could cost a man his reason, Onia considers what it would be like to let go and give up. Imagine, he says, a normal Sunday afternoon going awry and leaving a family in tatters. Without word or warning, all that a man has lived for is taken away. There are only three possible endings according to Onia’s dark fantasy: death, madness, or a lifetime of misery. The resilience of the human heart is nowhere to be found in Solitary Garden. The mind snaps. The spirit breaks. The fragile grip on sanity is lost. People grow old. People die. All that is left is a pair of pants hanging lonely in a closet.

Madness and depression have long been capable muses for artists and poets. Sylvia Plath knew madness intimately and left a beautiful body of literature documenting her struggle. “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead,” she wrote in “Mad Girl’s Love Song,” a poem published a decade before she stuck her head in an oven and gassed herself. In a 1962 interview, Plath remarked: “I believe that one should be able to control and manipulate experiences, even the most terrifying — like madness, being tortured, this sort of experience — and one should be able to manipulate these experiences with an informed and an intelligent mind.”

This sentiment, which implies a dedication to craft, is one other thing (beyond madness and depression as muses) that Onia shares with Plath. Plath’s writing, though motivated by bleak impulses, is precise. Her language has been described as “clean” and “crisp” — descriptors that also apply to Onia’s noirish photorealistic paintings. Solitary Garden is an insane asylum, but it is an insane asylum wherein every creased sheet and every wrinkled hospital gown is rendered by a focused hand.

The last thing Onia did before deeming his paintings finished was to burn specific areas on each canvas. The result of the process is a ghostly cloud of soot where a subject’s head should be, as if the head had exploded or spontaneously combusted. Onia explains that the black mark is a reminder of the irrevocable damage that a tragedy can inflict on a human being, of pain so great that those who survive it are forever changed. We may come back, he says, but we never fully return.

A specific story lies at the heart of Solitary Garden, bits and pieces of which have been told through Onia’s previous exhibitions. But that story is not

the point. And again, Onia’s thoughts mirror Plath’s, who can, with much more eloquence and grace, explain why “private wounds” should not be shared in public: “I think my poems immediately come out of the sensuous and emotional experiences I have, but I must say I cannot sympathize with these cries from the heart that are informed by nothing except a needle or a knife, or whatever it is. … I believe it should be relevant, and relevant to the larger things, the bigger things.” So, too, with Onia’s Solitary Garden, which welcomes visitors but implores

them to think about the lunacies of the world at large instead of the artist’s own.

— ll

*Litany IV (Moonchild) by John Zorn, performed by Mike Patton

WORKS

DOCUMENTATION