Aportraiture

(Raymond de Borja)

“The real victim of photography” Walter Benjamin recounts for us in his essay A Short History of Photography “was not landscape painting, but the miniature portrait.” Such was photography’s initial effect on portraiture, that, in a little over 10 years after the first photograph was taken “most of the innumerable miniature painters […] had already become professional photographers.” It has been almost 90 years since Benjamin’s short history, and in the intervening years, the hand that photographic techniques (and a little later filmic techniques) have had on the expansion of the field of painting, is inarguable. But the immediate, and obvious consequence of photography was that, instead of being an affront to painting, it had only added more objects to the objects of the world; a photograph became another thing to be painted. At its nascent stage, the photograph’s relationship to painting was that of a “technical adjunct.” Benjamin gives account of Maurice Utrillo who in 1910 “painted his fascinating views of Paris not from life, but from picture postcards,” and of David Octavius Hill, who painted frescoes from a series of portrait photographs that he himself took, and who, would later on become much more widely known for his stash of photographic aids than for his paintings. From these preliminary examples, painting’s interest in photography will take on countless generative turns along with the proliferation of modes and variants of the contemporary photograph: the film still, the screen capture, pictures on social media platforms, etc. In the 1960s, when Clement Greenberg asserted abstraction’s role as the primary mode of modernist painting, Francis Bacon painted from photographs and film images, and in effect generated other possibilities for the figurative in painting:

Interview 1, 1966

DAVID SYLVESTER: It’s interesting that the photographic image you’ve worked from most of all isn’t a scientific or a journalistic one but a very deliberate and famous work of art – the still of the scream from Potemkin.

FRANCIS BACON: It was a film I saw almost before I started to paint, and it deeply impressed me – I mean the whole film as well as the Odessa Steps sequence and this shot. I did hope at one time to make – it hasn’t got any special significance – I did hope one day to make the best painting of the human cry. I was not able to do it and it’s much better in the Eisenstein and there it is. I think probably the best human cry in painting was made by Poussin…

Allan Balisi operates in painting’s filmic and photographic spaces. He is aware of the questions that image making, replicating, and archiving technologies pose to the significance of contemporary painting practice, and he contends with these questions by making them the necessary conditions for his works. His relationship to filmic and photographic techniques has spanned his numerous shows and publications: in his show titled “In Between Open Fields” (Blanc Gallery, 2015) we find a series of paintings of images sourced from screen captures of low resolution, drive-in movies; in “People I Don’t Know, and Places I’ve Never Been” (Blanc Gallery, 2016), ink drawings of vintage photographs he bought from a thrift shop; and pronouncedly, in his picture book “Everyone Exists Forever” (Self-published, 2016), with its subtitle “Thirty Three Film Endings/ Thirty Three Drawings,” pages of drawings of the closing scenes of various films. While in most of his shows and books, the photograph takes on the role of source image (at times cited, though more often, not), a slightly different but nonetheless engaging dynamic between painting and photography is at work in his minimally designed book “Painting Study” (Saturnino Basilla, 2015). In “Painting Study,” Balisi presents us with pages of photos of an unnamed man “who from his initial static, standing pose,” he says “was then given the instruction to fall.” Yet we see that even in his photography work, the consistently muted color tonality, which we find in most of his paintings, persists:

Balisi takes more than source images from film. His process involves sifting through a voluminous amount of pictorial material, physical (second hand books, found photos, etc.) and virtual (streamed movies, online videos, etc.), zooming into and/or cropping out details from these images, then replicating them in tonally consistent painterly conditions; his selection procedure bears, in a number of aspects, similarities to the work of film editing, or more specifically to the composition of filmic montage.

But what value can the decontextualized image still have given our contemporary realities, realities that include the overabundance of images and the deliberate repurposing of these images with the intent to misinform? Perhaps we can look to the dynamic of image and gesture, through possibilities offered by Giorgio Agamben when he thinks of this dynamic via the cinematic image. In Agamben, gesture is neither a means to an end, nor the means as an end in itself. Although he locates gesture in the sphere of action, he describes it as the mode of action where “nothing is produced or acted [but rather, where] something is […] endured or supported.” Gesture then is a form of pure potential, a sheer condition for the possibility of choice, and therefore the possibility of an ethics. For Agamben, the value of gesture is that, there is, through it the immanent reminder that “there is no essence, no historical or spiritual vocation, no biological destiny that humans must enact or realize.” Through gesture “something like an ethics can exist, because it is clear that if humans were or had to be this or that substance, this or that destiny, [then] no ethics would be possible – there would only be tasks to be done.” Agamben finds in cinema, a paramount method for the recording of gestures. By emphasizing that a film, in a nod to Gilles Delueze, is composed not merely of sequences of static images, but rather by “image-movements” themselves, he underscores the capacity of the cinematic image to exhibit “pure mediality,” to make “a means visible as such.”

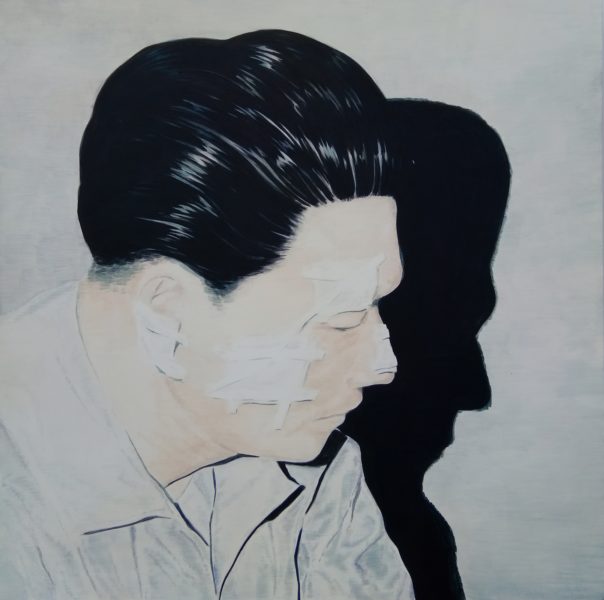

The images in Allan Balisi’s “The Smallest Convenience” are drawn from medical books, hospital archives, first aid brochures, instructional medical videos, and similar such sources. “I am still interested in narrative, but with more interest in the idea that the viewers will make what they will of the images rather than attempt to reconstruct the original narratives from them,” Balisi speaks of a plausible effect of his work. His interest then is not in narrative per se, but in the gestural potential of the image to open up narrative, or, to push the idea further and perhaps more variously, his engagement lies in the images’ capacity to merely open something up. His works in “The Smallest Convenience” are hardly bound by narrative, but are tied rather, and to a greater degree by a particular typology: bandages, prostheses, gauze, the injured figure given medical attention, the medical worker in the act of preparing various medical implements. Rendering these images in the consistent tonality that pervades his works, our attention is drawn away from the pictures’ connotative implications, and towards the movement of images from one denotative system to another, that is, from the denotative system of medical instruction to a signature painterly rendering of particular types. In “The Smallest Convenience,” the type in focus is that of the figure of and around the damaged body.

We find in “The Smallest Convenience” what are quite possibly investigations of gestures and gesturality: in “Viridian State of Grace,” a woman is absorbed in what seems like the preparation of bandage from gauze; someone is attending to an injured knee in “According to Ovid’s Description of Feathered Cloaks”; a hand is laying down what is likely a model for prosthetic arms in “To Identify as Imitating.” Gesturality is manifest not only in Balisi’s figures that are caught mid-action, but even in his method of painting as well. Of recent changes in his painting approach, he says: “I used to work by applying layers of paint, then scraping the layers off to achieve the subdued color of my paintings, but in my more recent works, I produce the subdued effect by a layer-by-layer application of thin, diluted paint.”

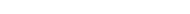

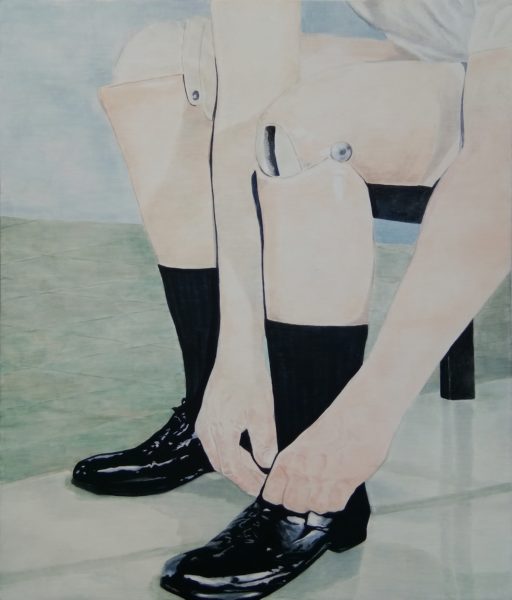

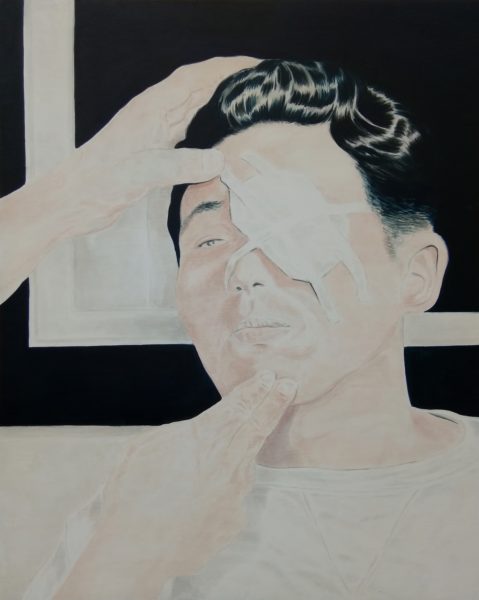

There is a marked expressiveness of details in Balisi’s paintings. We notice for instance the attention that he gives to his figures’ heads of hair, how detailed the locks and waves of hair are, for examples, in “Mending Figure” and “Pursuing the Sight,” or how the expressive creases of hair of the woman-figure are echoed in the green folds of dress in “Viridian State of Grace.”

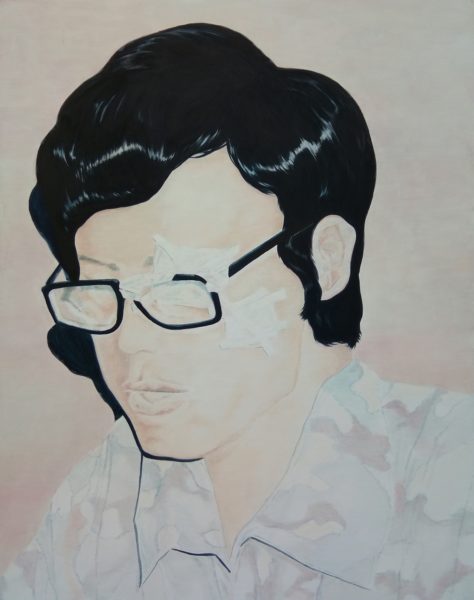

It is also quite noticeable that Balisi’s figures rarely fully expose their faces – a motif that persists in his shows and publications. In certain extremes, Balisi’s figures face away from the viewer, exposing only their characteristic heads of hair. Often, his figures attend to tasks that seemingly require their absolute focus, giving them no chance to turn towards what could-have-been the depictions of their faces. In a number of instances, the figures have their heads slightly bowed down, or turned to an edgewise angle. This particular motif is one we find in “Triumph in Disguise” where we catch the slight profile of a man wearing a pair of glasses that are tenuously held by gauze. Yet the man’s face seems to communicate nothing beyond the adhesive bandages covering up his bruises and wounds. In what may be a playful turn, we find that there is much more attention given to the details of the man’s varicolored, camouflage shirt. Balisi comments on portraiture by excluding the face, by locating expressiveness in gestures and in creases, by giving extraneous details the expressive qualities we would normally find in the face.

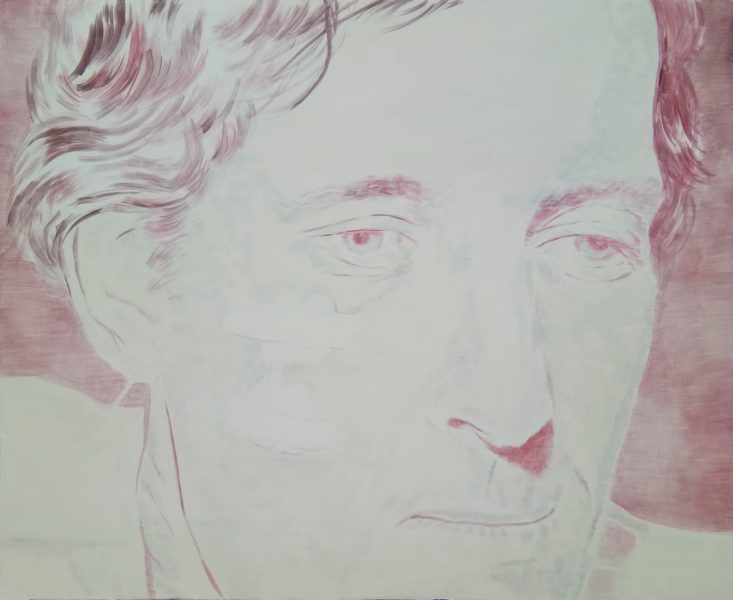

The closest to standard portraiture that Balisi gets to in “The Smallest Convenience” is with the painting that shares the show’s title: “The Smallest Convenience (Beautiful, Noble, Necessary).” Here we have a man still slightly looking edgewise, but this time remarkably with his eyes fully exposed, his face given further expression by his well-formed nose and lips. His face is bathed in reddish light, strands of his hair slightly cov the top of his right ear. In the subdued red light of overexposure, we find patches of green pigment in the skin of his forehead, chin, and cheeks. But with a closer inspection of his cheek, we find a wound dressing, an adhesive bandage likely covering a scratch or a bruise, repeating the show’s thematic. Perhaps, and somewhat playfully, Balisi reminds us that with the exponential proliferation of the image, portraiture more and more becomes another system of typology.

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. Means Without End: Notes on Politics. Trans. Vincenzo Binnetti and Cesare Casarino. Minneapolis, MN: Univ of Minessota Press, 2000.

Agamben, Giorgio. The Coming Community. Trans. Michael Hardt. Minneapolis, MN: Univ of Minessota Press, 2013.

Benjamin, Walter. “A Short History of Photography.” Trans. Stanley Mitchell. Screen, Volume 13, Issue 1, 1 March 1972, Pages 5–26

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon. London, GB: Thames & Hudson, 2016.

Works

ACCORDING TO OVID'S DESCRIPTION OF FEATHERED CLOAKS

AIMED AND MISGUIDED

CRYSTAL

GETTING ALONG

MENDING FIGURE

MOST TENUOUS DETAIL OF OUR LIVES

PURSUING THE SIGHT ALONE

SMALLEST CONVENIENCE (BEAUTIFUL, NOBLE, NECESSARY)

SMALLEST CONVENIENCE (MOST ADORING LOVERS)

TO IDENTIFY AS IMITATING

TRIUMPH IN DISGUISE

VIRIDIAN STATE OF GRACE

Documentation