Dog Years

Allan Balisi

Blanc, 2023

Dawn of August 29, 2021, the rainy season, I was in a rental car going to the animal clinic with my dog. He was running out of breath, lying down on my lap, covered with a blanket, with his cheeks in my arm. He was facing the car window to get a glimpse of the sun—rising and stuttering in between establishments. When we arrived at the clinic, I was advised that I needed to confine him. I was told that the possibility of him surviving was cut down to half. Promises were made, assurances were laid down, and after a few hours, my dog was gone. I even blamed the sun for rising that day—wrong time,

wrong season.

In Dog Years, Allan Balisi is an autobiographical contemplation exploring two thematic strains across a collection of paintings, going as far back as his childhood in Isabela, tying the freedom of this time with the constraints of adulthood. Choosing to capture the essence of these pervasive thoughts and personal histories in innocuous objects, Balisi imbues each picture with the life and memories he has carried across his life, and the ongoing pursuit of the joys and reprieve he knew but life threatens to make

him forget.

- Attachments and Strings

“Home Run” is a picturesque representation of the nostalgia of childhood. Memorializing the magic of a vacant lot (this particular one: the lot across his mother’s house in Isabela; his grandfather’s house in sight beyond that) that perhaps is only visible to a child — playing a form of baseball as inspired by Sandlot, catching insects, flying kites, and other activities reliant on something as simple as the weather. “Whenever I see butterflies, dragonflies, or familiar stray weeds and plants, or whenever I feel the sun on my face on a hot afternoon, I think of the years when we were tireless and cheerful — memories of hitting hard a baseball, making a home run, touching the bases freely.”

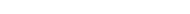

For someone who has never ridden a ferris wheel, Balisi curiously paints one in “Beside You, Steady Breaths”. Acting as a stand-in for Balisi’s “never-ending loop of ups and downs” in daily life, the ferris wheel becomes a ride he is forced to ride — no longer a spectator, but an unwilling and inevitable participant, anticipating a halt to the endless cycle of responsibilities and obligations of adulthood.

“Accumulation of Gestures I (Bonfire)” captures the act of preparing for a bonfire—once again a signifier of something exciting and celebratory, another marker of childhood. Bonfires, prepared by his mother, served as a vessel to carry away unwanted waste, and yet Balisi kept the fires burning with old books, twigs, objects that have served their purpose. “Accumulation of Gestures II (Pond/Ponding)” represents the fear of losing Isabela to La Niña and forest denudation. Parts of Ilagan, Isabela are sinking, the slow loss of which felt like time itself was disappearing. The landscape in “Home Run” holds water seasonally, due to heavy rain. Like Ilagan, the land loosens up, but also brings solace to small fishes and frogs. Landforms follow the shape of the seasons, changing as the world changes, holding in their bodies the changes that surround them.

Paying homage to the collection of drinking glasses that populate a typical Filipino family’s home, “Crystal Place” shows the anticipatory fulfillment of things to come. Growing up in a household filled with glasses far outnumbering the residents of the home point to the expectation of celebration and abundance: a chance for these cups to be filled again, if only for a short period of time.

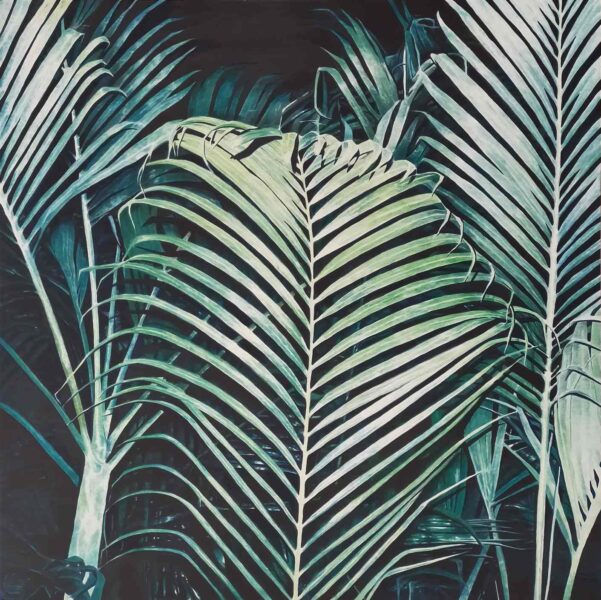

“Hundred Swords” is a painting of Palmera plants growing alongside his ancestral home. These plants grew to destroy the cement wall of their home — “as if creating space to nurture life” — with the wall of foliage serving as a temporary home to the maya and quail who come to nest within the protection of the fronds. As a child, Balisi looked for nests inside this makeshift sanctuary, sometimes finding eggs and returning nestless fledglings to their homes.

“Interplay Between Us” depicts the pursuit of meaning through connection, our personal formations made possible through relationships.

“Freedom isn’t the act of shedding attachments, but the practical capacity to work with them, to move around in their space, to form or dissolve them… Freedom to uproot oneself has always been a fantastic freedom. We can’t rid ourselves of what binds us without losing the very thing to which our forces would be applied.”

— Joyful Militancy: Building Thriving Resistance in Toxic Times by Nick Montgomery and Carla Bergman[1]

- Myths, Guides, Making your own maps

“Maybe you stumbled into it by accident, once, amazed at what you found. The old world splintered behind and inside you, and no physician or metaphysician could ever put it back together again. Everything before became trivial, irrelevant, ridiculous as the horizons suddenly telescoped out around you and undreamt—of new paths offered themselves. And perhaps you swore that you would never return from whence you’d come, that you would live out the rest of your life electrified by that urgency, that thrill of discovery and transformation—but return you did.”

— Expect Resistance: A Crimethink Field Manual by Crimethinc Worker’s Collective[2]

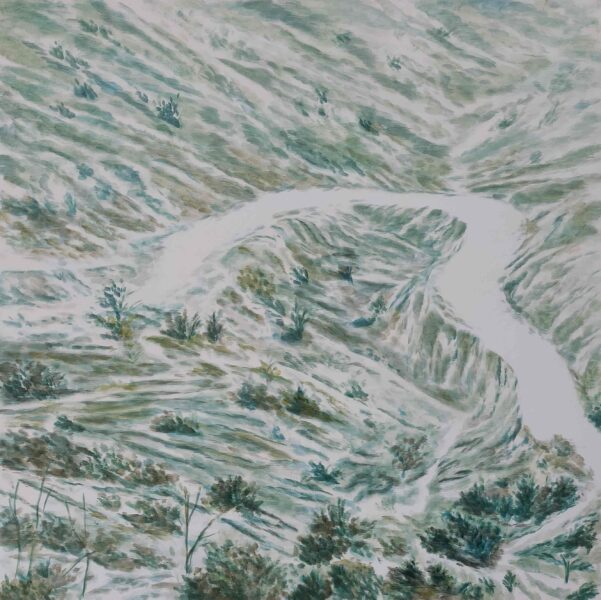

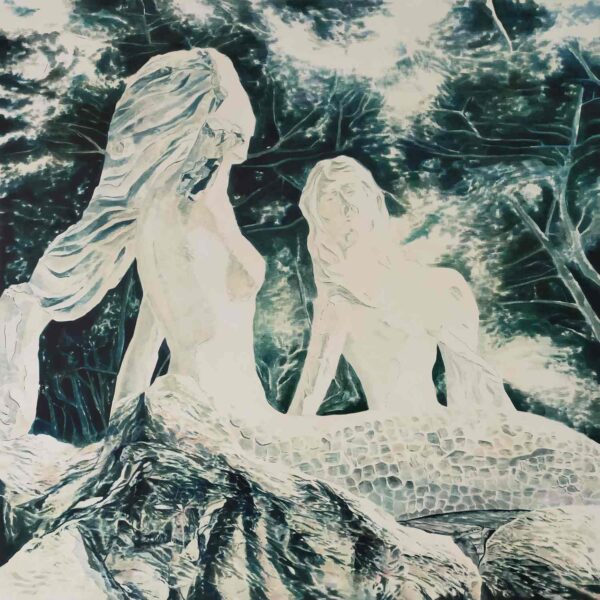

In “Monuments”, Balisi captures the likeness of mermaids, a creature used in their province to scare children away from swimming or diving in the river. Utilised as a cautionary tale, abduction by these creatures replaces the fear of drowning. These statues bear an imposing presence, though the unrelenting waves of the sea will wear away these stones eventually. “Guided by Hands I” presents a different effect of touch: the comfort imparted by a pat on the head, by touch.

The tawa-tawa plant, abundant in Pangasinan, is the hero of “They Abide and They Endure”, a portrait of resilience and persistence. Balisi had asked a relative from the province to bring some into the city, as tawa-tawa is known to be a medicinal plant and a cure-all for many illnesses. The uprooted tawa-tawa plants travelled six hours from Pangasinan to Manila, replanted in the hopes that they would survive and grow in the city. The first plants did not; however, months later, the plants began sprouting in places around their house: the laundry area, the backyard, beside a wall, and springing from the soil in other potted plants. While they never live for long periods of time, some part of them finds a way to survive, ready to heal, not unlike the bank of memories we return to again and again when we need to endure.

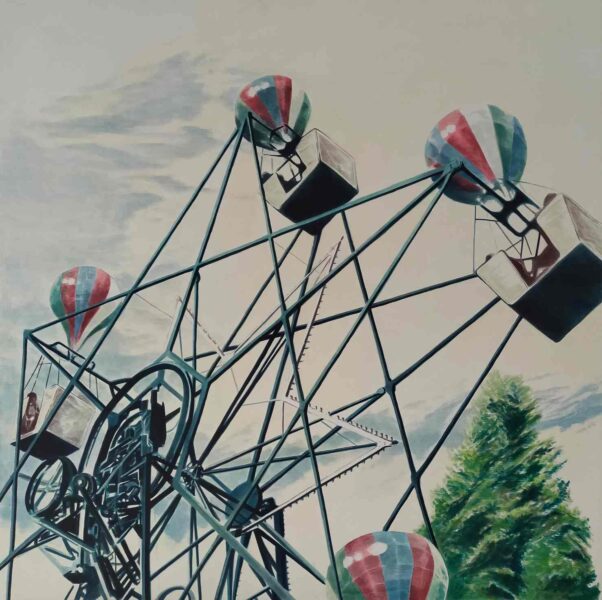

Depicted in “Geography” is a zig-zag road — reminiscent of Dalton Pass, a road and mountain pass that joins the provinces of Nueva Ecija and Nueva Vizcaya. It is the only route connecting Balisi’s province, Isabela, to Manila, where he currently resides. It is also the site of the Battle of Balete Pass, during which thousands of Filipinos, Americans, and Japanese soldiers perished in the second World War. The road is treacherous to travel, making those in transit prone to many dangers and accidents, though a necessary journey to reach one’s destination.

We are bound by the time and spaces we live and move within. There are fewer and fewer free undeveloped spaces left where we can let our bodies and minds run free, and the motions we go through in life rarely ever take us to these places, places which ultimately enrich our lives and give meaning to it. The void of desperation and unfulfillment grows, as we lose these free spaces, with the Internet seeming to remain as the “final frontier” — the last “free” undeveloped space left to explore, on the condition of voluntary amputation: the mind existing and exploring with the body detached and stationary, sitting in front of a glowing screen with our other senses numb and unused, settling for the limited freedom within reach.

Balisi believes these calls for the invention of new games: new games to be played in conquered areas, a reclamation of the meanings that have been prescribed and are being followed, calling to bring us together, out of confinement and isolation. We need to recall the magic of a vacant lot, freedom from the tyranny of synchronization with the rest of the world. “Guided by Hands II (Tactile Map)”, for example, celebrates the maps we make and the journeys we all take — all different from one another’s and singular — without diminishing one’s own.

“Autonomy and The Seasons” is a painting of a typical Christmas ornament, meant to adorn households for the holidays, though often overstaying their welcome well into the turning of the seasons, sometimes even staying forever. “These symbols change as you interpret them differently,” Balisi writes, resisting the meanings of these images that heavily lean on cultural prescriptions. Like paintings, each image expresses ideas, emotions, aspirations. While conveying these things, they are often interpreted wildly differently, depending on who views them, according to their personal histories and journeys. And yet, a single image can perfectly encapsulate a message, even with the billions of possible interpretations: a representation of our own truths, resonating with our deepest desires.

A hand clutching fallen branches is what is painted in “Picking up the Branches”. Twigs and branches that were once attached to a tree and were beyond reach are gathered in a hand, collateral damage of natural decay or the tree withstanding a storm.

–

Ultimately, Dog Years is a collection of memories, images, and stories, embodying the feeling of being unmoored, during tough times of uncertainty and vulnerability, but also the relief that comes with the presence of a community. We can unburden and support one another: waves of love help break the stones, something joyful to fill empty lots, overgrown plants provide home and sanctuary, a pat on the head provides reassurance that this, too, will pass. Perhaps, tomorrow, the sun will rise differently.

These paintings are taken from real places and memories, Balisi’s personal experiences and interpretation of the world. Through these, there is his hope that whoever views them will be handed a guide, a map, or even a liberated territory that is free to be interpreted accordingly.

When we talk about “dog years,” there is always a misconception of time, a misalignment of how we perceive the actual length of time, and what this period actually holds. In “dog years” it is not a short period of time: it’s a lifetime of good memories to cherish. Like a game of cat’s cradle, these memories configure into a thousand forms — however long or short that may be, to make our life more like the one we would like to live, taking to heart the precarity of the time we have, and the time we have with each other.

Carina Santos

[1] Joyful Militancy: Building Thriving Resistance in Toxic Times by Nick Montgomery and Carla Bergman, 2017. AK Press.

[2] Expect Resistance: A Crimethink Field Manual by Crimethinc Worker’s Collective, 2007. CrimethInc. Workers’ Collective

Works

Documentation