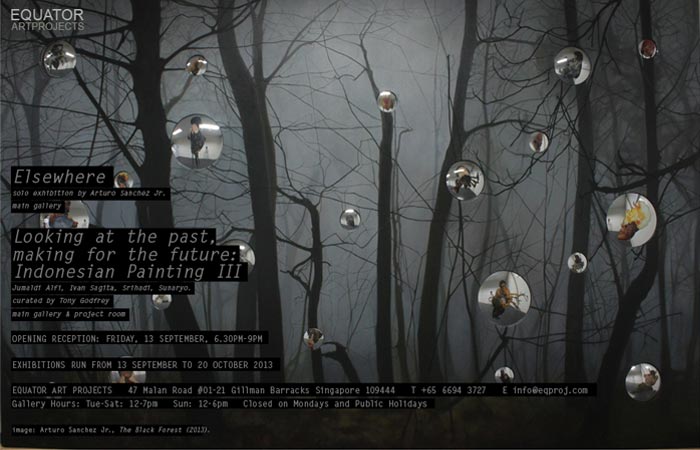

Arturo Sanchez Jr.

Equator Art Projects Singapore

September 13 – October 20, 2013

Curated by Tony Godfrey

SANCHEZ ESSAY

For twenty-five years I lived in London and I lived with four mirrors. The first I looked at each morning when I shaved and examined my face for signs of age or tiredness. It was a moment of concentration – don’t cut myself!– and either reflection – Who am I? What am I? How am I today? – or of panic – I am late for work again!

Every week I would walk from work to my bank to get money to live on but I had artfully planned it that the quickest route to the bank at the south end of Trafalgar Square was through the National Gallery. Every week I would take time off to look at one painting and think about it. Sometimes I would stop and look at the most famous mirror in art history – except that it isn’t a mirror but a painting of a mirror, that in the background of Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Wedding. We stand in front of the painting and look at the couple who are being wedded, but then looking deeper we see ourselves in the mirror – or others standing where we would be were it a real room so it seems we see ourselves dressed as fifteenth century people coming to greet the happy pair. Playing a little on whom these people could be, Van Eyck has written above the mirror: “I was here”.

(A similar game is played out in Velazquez’s studio portrait Las Meninas where the artist portrays himself painting the king and queen. We see them indistinctly in a mirror behind him and with a certain shock we realise that we art watchers are standing where they too would have stood to be so reflected in the mirror. This is all as Michel Foucault showed in his analysis of the painting in his book Les mots et les Choses, a very serious game about identity and how one sits in the world.[1] As he points out this mirror is, as is that in van Eyck, as active as an eye itself, seeking out what we cannot see.)

On occasion rather than heading back to work I would wander along Pall Mall to the Courtauld Institute and look at Eduard Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergeres. Again, though it is not immediately obvious that there is a mirror in the painting, once realised we seem to see ourselves – but we are not visitors to a posh wedding or the studio of the official painter to the Spanish king. The whole back of the bar was one curved mirror but now the role of alter ego is (as art historian Tim Clark pointed out) a rather sordid one: a barmaid at the Folies Bergeres probably supplemented her wages by part time prostitution so the man leaning towards her is probably saying something like “are you working tonight?” or “fancy going to Geylang?” We are implicated not only in a very complicated and sophisticated pictorial puzzle but in problematic social and sexual politics.

Mirrors implicate us in the problems of the picture. They trap our reflection. In art mirrors can be active, not just passive reflectors. A painting of a mirror is an uncanny thing: it purports to reflect but does anything but that.

Occasionally I went the other direction under Admiralty Arch and had a drink in the ICA bar in which there hung for many years an exceptionally large mirror. I enjoyed the fact that few others realised that this had once been a work of art, one by Gerhard Richter no less. Invited to participate by critic Michael Newman in an exhibition entitled The Mirror and the Lamp Richter had asked him to install the largest mirror obtainable commercially in The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition in which he showed that whereas traditionally literature was usually understood as like a mirror, reflecting the real world, for the Romantic writers like Keats or Wordsworth writing was more like a lamp. Literature was not mimesis but where the light of the writer’s inner being flooded out to illuminate the world. The same binary, Newman argued, was at play in contemporary visual art.

Inevitably Conceptual art which often reflected on the nature of art and representation was obsessed with mirrors: Robert Morris, Robert Smithson, Giulio Paolini, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Michael Craig-Martin, Art and Language, Roberto Chabet being but a few who employed mirrors as key elements of art works.

From Van Eyck to Chabet there is a long history of the mirror in art used both as a device and as a metaphor. (Also, we should never forget mirrors are also every day household objects.)

What does Arturo Sanchez add to this history?

Technically he does something very novel: he does not just embed mirrors in his work, nor does he just represent them or painting over them, what he also does, as in many of these work, is scratch away the silver at the back of the mirror and insert collage elements.

This is not just a mere technical novelty; it inverts or diverts the Mirror/Lamp dichotomy: the work is simultaneously both mirror and lamp. We look at the mirror and see ourselves but also something that is not in the room beside us.

This is both beguiling and hard to pin down. Furthermore, there is something strange in the way in Silver Tears and the Black Forest the mirrors are laid out in an apparently asymmetrical pattern but one that is in fact balanced, as if ready to rotate – or as if two warriors were circling each other, eyeing each other. But what do they see: their own reflection or a doppelganger?

Even when we look at the two medium size paintings on mirror, Kindred Spirits and Veiling Reflection, we are not sure if the echoed girl or boy is reflection or a doppelganger, an illusion or a reality. Perhaps they are the imaginary friend or guardian angel in disguise. Both paintings do however have a cunning trap, surreptitiously referencing Asher B. Durand’s Kindred spirits and Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the rocks. Durand’s 1849 painting showed the artists Thomas Cole, who had died the previous year with the poet William Bryant in the virgin forests of America, communing with nature and in harmony with each other. (The title is derived from a poem by Keats that describes such friendship in nature as the “highest bliss of human-kind”.) But though the painting commemorates friendship and harmony it has come to epitomise contested morality as well as the Hudson River school of painting. Bequeathed to New York’s Public Library, they sold it in 2005 for $35,000,000 to the private collector and billionaire Alice Walton who keeps it in her private museum in Bentonville Arkansas. There are two nearly identical versions of Leonardo’s painting, one in London, one in Paris. An exhibition in London’s national gallery where they were hung on opposite walls failed to resolve the endless discussion as to which is the prime or first painted version – or, which is the double.

All this does not explain the paintings; rather it enhances their resonance. Although the mirror may be in recent art more associated with conceptual practices, Sanchez is above all an intuitive artist, not someone fulfilling a pre-determined project. He uses images from anywhere, the origin does not matter to him. What matters is what it can do.

We may recall that Borges complained in his 1940 story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” that “mirrors and copulation are abominable, since they both multiply the numbers of men.” These mirrors, that are not wholly mirrors, do not do that: they do something else. What a mirror cannot do is Transform – it will always, like the mirror in Snow White, tell the truth – yet these paintings are transformations!

There is something poetic or even visionary

about his choice of images to collage into the pictures, emerging in the small paintings like baroque ectoplasm from the faces or bodies of unsuspecting individuals – or like tongues of flame. This can seem filmic. It is a familiar trope in movies for different images to emerge as if in a dream from pool, window or a mirror. Such reflective surfaces seem the natural home for phantasmagoria.

It should be noted, and it is not insignificant that these are beautiful objects, not just in the fine craftsmanship (these are very labour intensive works) but in the way opposites – colour and grisaille, reflection and representation, order and the visionary, – seem albeit temporarily reconciled and in harmony.

©Tony Godfrey. 2013.

[1] Michel Foucault, Les mots et les choses. Paris, 1966. Bizarrely translated into English as The Order of Things not as The words and the things.)