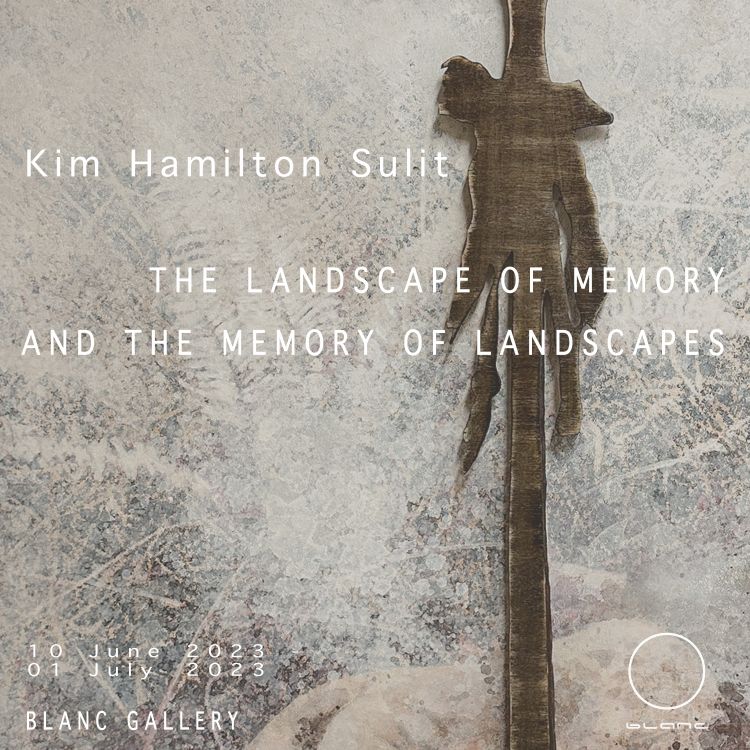

The way out is through:

The Landscape of Memory and the Memory of Landscapes

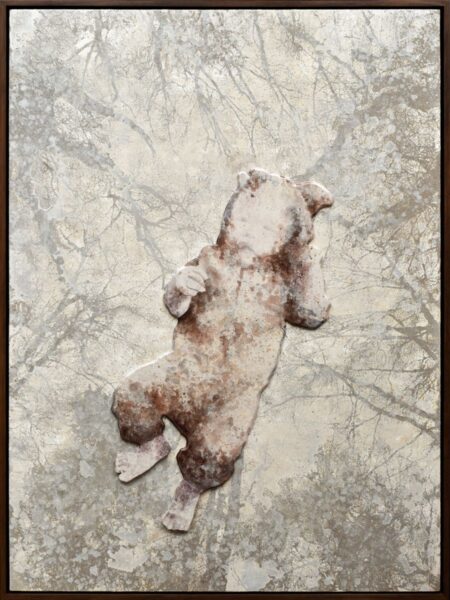

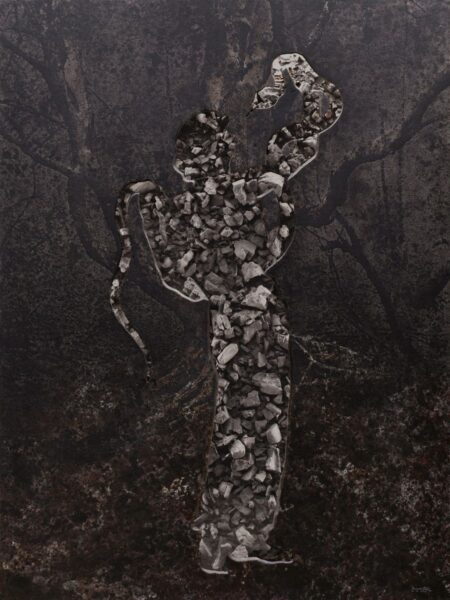

Landscapes remember: Ancient events are engraved in the grooves of ancient bedrock, new islands tell of a seemingly Atlantean life before the tides shifted, and the same ground where dead things spend their final days becomes the same fertile ground for rebirths. The human body is, similarly, a receptacle of memory. Contemporary artist Hamilton Sulit does the daunting task of reliving all his experiences from the past years using acrylic, charcoal and LED lights to create paintings and assemblage portraits. Creating “a collection of visual images about the human condition in particular to the idea of our existence and domestic experience”, Sulit’s pieces for The Landscape of Memory and the Memory of Landscapes were made with the deliberate attempt to “examine the relationship of our personal experience and shared memories, our attachment to things and surroundings that shaped us through time.”

The idea of title and layouts were inspired by imagining taking on the point of view of a CCTV operator—one with a panoramic view of the subjects within his field of vision, like “various channels of memory”. From narrative to concept and process to execution—for Sulit, this series is a journey through the landscape of time and memories, recalling and reclaiming every significant experience he’s had the past few years that has played a hand in shaping him. But the path forks off at some point, with some of the works expressing vague memories that the artist still attempts to understand, as to whether they were based on real events, or just imagined projections of certain times and the strong feelings and sensations attached to them.

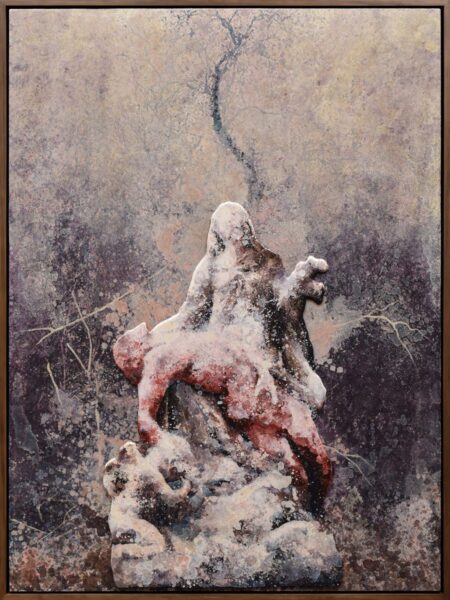

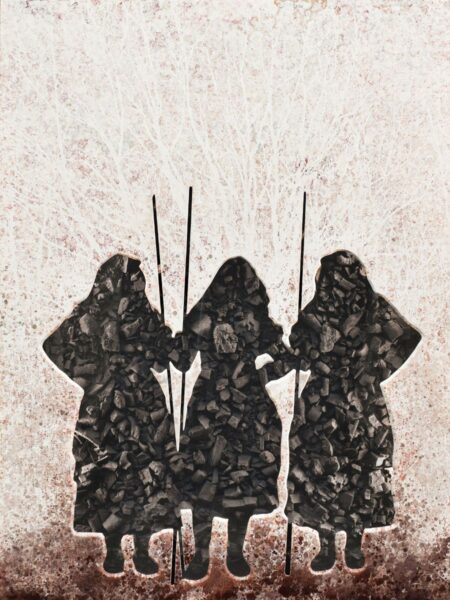

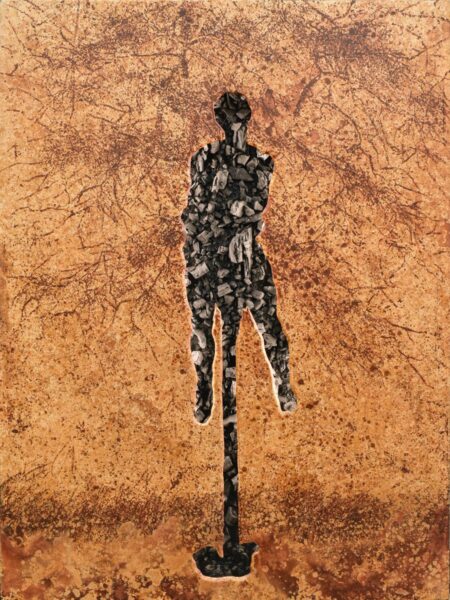

Curiosity driving him to go out and through with conflicting bleakness and aplomb, he dives headfirst into the memories that left deep scars and still ache palpably from time to time: a tribute to the three women that raised him, as represented by his version of the Three Graces of Greek literature; losing his grandmother at around the same time he found out he was going to have a baby; and forlorn scenes that resemble pain and departure.

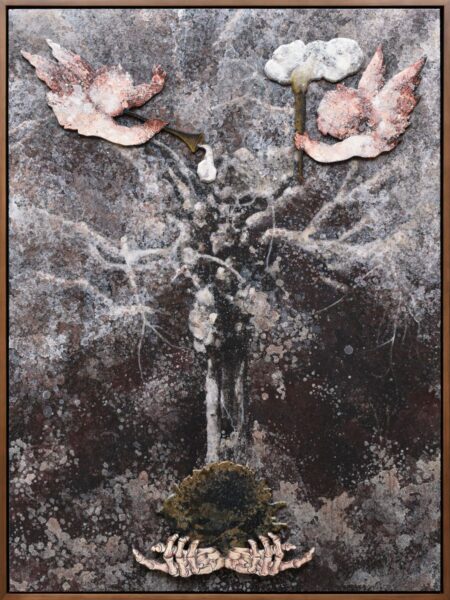

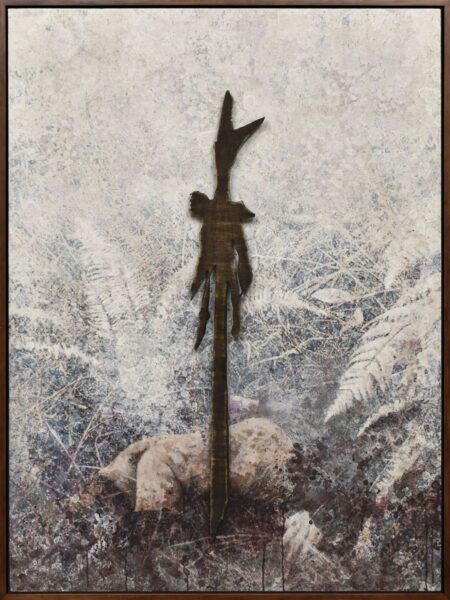

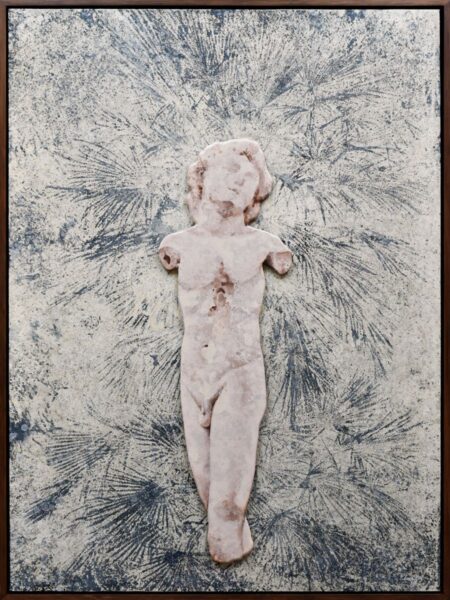

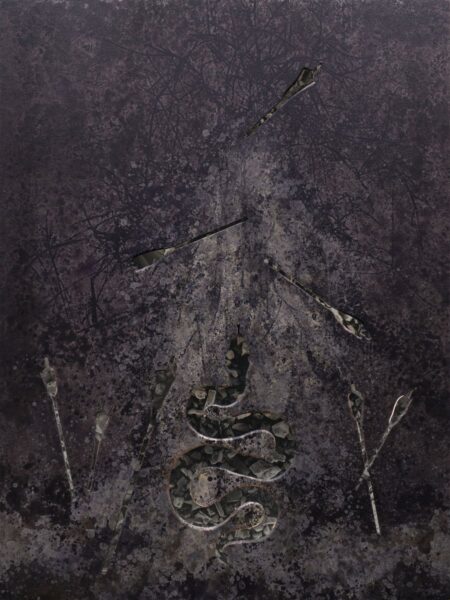

Some works apply more specific imagery and objects as a point of thought-processing: works inspired by Magritte’s works “Memory of a Voyage” (1955) and “Young girl eating a bird (The pleasure)” (1927), depicting the attempt to conquer fear and danger; a man with sword, prompting thoughts about mortality and the nature of life; a pile of leaves with snakes and arrows, pointing to how we sometimes “become part of the surroundings we belong to”, as if we were the subjects on display in this landscape of experience; and subdued trees and landscapes, which Sulit looks to as the watchers of time-the constant observer of everything we’ve been through, reminding humans as being “students of nature and time, with our surroundings as the masters that help us grow”; and an angel, contemplated on with an inquiry about life—questioning the weight of difficult times out of exasperation, wondering if this is this is the default difficulty level of life, or if the gods have been tinkering with the settings for meaningful, cinematic story arcs, or—god or some other being only knows—sheer, cosmic entertainment.

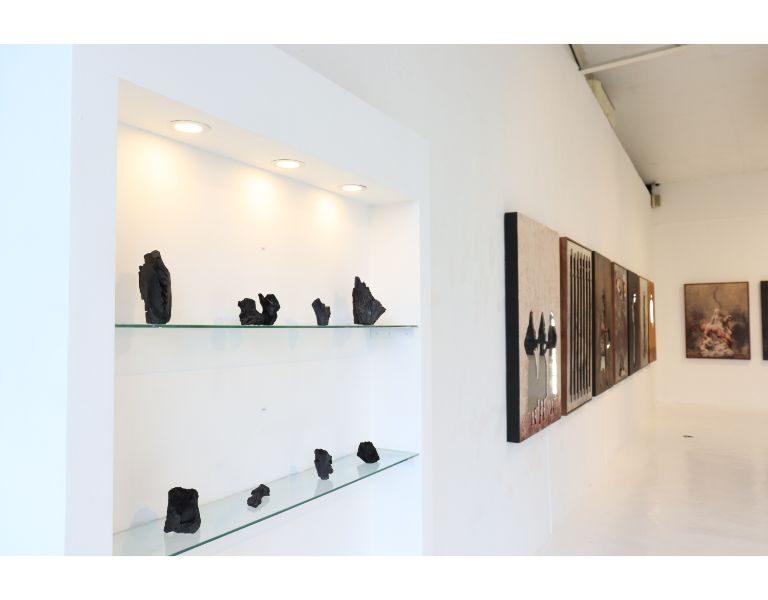

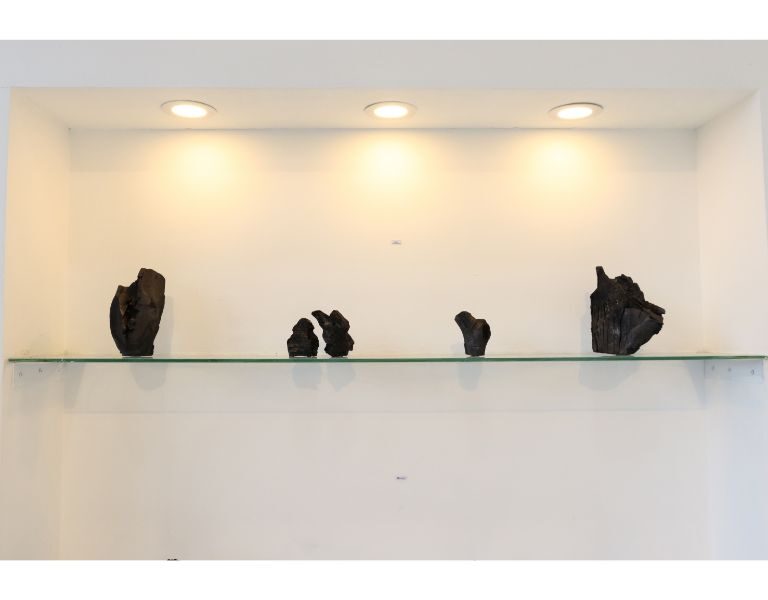

Sulit’s use of the elements of fire are intentional: A head—aflame in a flesh-like shade—symbolizing an extension of (or our longing for) life, hoping that the flames maximize the wick if we really only live as long as we burn. On the other hand, charcoal is his metaphor on our experiences and the human condition: With the remains containing bits and pieces of memory. For Sulit, we’re just flesh floating in the air without our memories. “Memory is what makes who we are. Our memory is our soul.”

Every texture, tear, and scratch tells of all the moments that—whether willingly or unwillingly—shape the physical and metaphysical spaces that we occupy. Like muscle memory, the body remembers: which is pain, which is joy and which are the habitable Goldilocks Zones that allow us to live in the constant fluctuation of both.

-Nikki Ignacio

Works

FIGURE OF MEMORY I

FIGURE OF MEMORY II

FIGURE OF MEMORY III

FIGURE OF MEMORY IV

FIGURE OF MEMORY V

FIGURE OF MEMORY VI

FIGURE OF MEMORY VII

FIGURE OF MEMORY VIII

FIGURE OF MEMORY IX

FIGURE OF MEMORY X

FIGURE OF MEMORY XI

FIGURE OF MEMORY XII

FIGURE OF MEMORY XIII

FIGURE OF MEMORY XIV

FIGURE OF MEMORY XV

FIGURE OF MEMORY XVI

Documentation