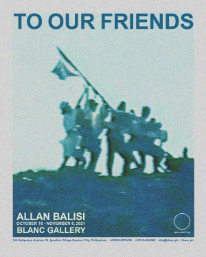

To Our Friends

Allan Balisi

“There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt…”

— Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984)

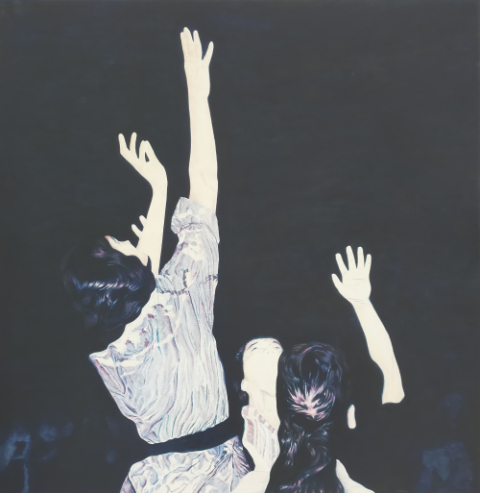

To Our Friends is not a call to action for resistance, per se, but the paintings presented herein represent ongoing quiet conversations that make the connections between resisting and thriving. Jumping off ideas explored in two self-published material, namely For Heaven’s Sake, Put That Down, Comrade (2021) and Painting Study: Excerpts (2020), Allan Balisi seeks to understand the ways in which we relate to each other, through movements at play today — which are often reactions or based upon some pre-existing idea — and the barriers to collective transformation.

The title — To Our Friends (borrowed from The Invisible Committee) — already implies a moving away from isolationism that is perpetuated by capitalism and the oppressive systems that are set in place by the State. In addressing a group with a sense of familiarity and kinship, it actively resists the despair set in motion by the inescapable “machinations, oppressions, and attacks” by the very recognition of a world beyond the self, of a community that finds moments of stillness, as well as moments of transformation.

Balisi writes, “This show is about connections, about echoes.” It is an acknowledgement of “uninterrupted survival and resistance,” and this is reflected, foremost, in the very selection of the images he has chosen to portray: “movements and moments that move people forward. Everyday.” Intending to build on what has already been said, driving shared ideas and sentiments forward as an ongoing reminder of insight, despair, and joy. Balisi’s images are “already manipulated before they hit the canvas.” This collection of images — mediated source material, vintage photos, press photographs, film stills, and his own photographs — is participatory. “I am led along by my source of images, as they manifest themselves,” Balisi writes, “rather than just executing them as if they were already resolved or preordained.”

The selection of images are grouped in categories that recognise painting as a vast number of things, “combining rigour with accessibility.” In pairing images together with titles bearing pointed sentiments towards these themes, he effectively thinks through these ideas and brings one along for the ride.

In “The Urgency of Making Kin,” Balisi invokes both Donna Haraway and Jose Lacaba, depicting a group captured in a joyful pantomime. In the midst of a struggle, here, he reconstructs the space into something where good can move out, a space made by people gathering together, refusing to blindly accept what has been made available, and placing trust in on another, towards a path of transformation. “If your heart is free, the ground you are standing on is liberated territory,” Balisi insists. “Defend it.”

“Paved With Good Intentions” introduces the recurring imagery of burning cars and wreckage present in Balisi’s work, something he has previously taken to portray unattained pursuits. This one in particular is taken from a press photograph in 1972, signalling the beginning of Martial Law in the Philippines. For Balisi, it represents people’s despair and desire, and “an uncompromising rejection of the prevailing order,” which opens up the possibility of imagining another reality. In wreckage and destruction, there is hope. In this image, the burning car is in view of an open gate, implying the presence of a spectator.

More frames of possibility opens up with the invisible barrier giving way in “Spell.” With a broken window, the spell of segregation is broken, too. Broken windows reterritorialise spaces, in that the gulf between security and vulnerability — a half-inch plate of glass — is somehow crossed.

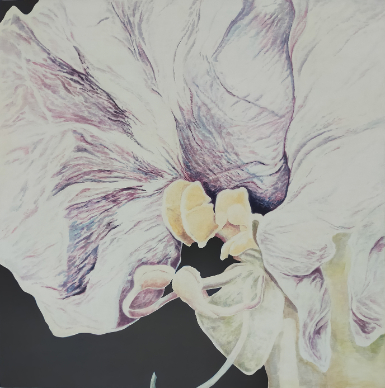

Another painting of a gathering is seen in “Seek no adherent, but accomplices,” where they obscure a sign, abstracting any obvious reference to ideas or movement. Here, Balisi elects to portray that intersection between love and anger: two non-mutually exclusive reasons for gathering together. It is a painting that reignites the feeling of collective power, a reminder of the power of everyday acts of resistance, and how these small acts can be radical in that they move people onward.

“Affect” is a stand-in for the loss of function for objects such as fountains, which used to provide communal drinking supply, and in this case, the image itself: where an image becomes just an image, rather than a tool by which a message is delivered. When a figure transforms from something with function to something ornamental, it’s akin to progressive movements losing power, becoming “empty epithets” that threaten and distract from what is really at stake.

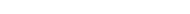

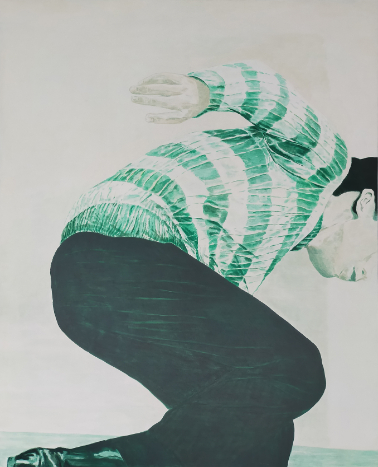

Throughout To Our Friends, Balisi captures the figure in the middle of moving. “The Self-enclosed Individual is Fiction” calls to mind the image of Saint Sebastian, shot with arrows, both figures caught in motion, and not quite in their final moments. “Enact” sees an actress onstage, in the middle of a performance. In the figure in “Epoch” is encapsulated that moment one decides to move: the beginning of everything. Even the flower in “Reminder” is preserved in a particular state, paused in motion.

“Transformative potentials are always already present and emergent,” Balisi says. “It’s a matter of tuning, tending, activating, connecting, and defending these processes of change.” Movement in the form of small radical acts add up towards an upending of the dominant order of things.

Ultimately, To Our Friends leans heavily on the idea of brokenness being an opening for something better, of positive growth in a site of loss. Through his chosen medium of communication, Balisi examines the role of painting — as gesture, as a space, as tactic — in engaging with and affirming contemporary currents of thought, “drawn from acknowledging the historical violences.” He uses it as a vehicle, to impart a specific message, “to represent uncertain yet reassuring transitions: a way of defining a feeling.” He embraces the intimacy painting offers and chooses not to be limited by projections on the medium, moving with renewed respect for an image that takes time, effort, and freedom to create.

“Those I’ve never met who, though far, are never quite distant” is an homage to Théodore Géricault’s “The Raft of Medusa,” a beacon to call to arms, in recognition of the power of community and organisation. It is a reminder of the presence of one another, never alone in our collective struggle; perhaps even happy, together, despite everything. In the calamansi tree in “Emergent Forms of Life In The Cracks of Empire,” we see the abandonment of “corrosive practices,” choosing instead to support and grow together. Unencumbered by the ways in which we hurt one another, we resist and we survive. The ribbons in “Overlaps and Resonances” signal the connections, continuation, and celebration. After everything that’s happened, it seems to say, it cannot end here.

-Carina Santos

Works

Documentation